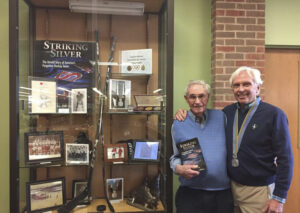

It was 1941 and Boston Olympics General Manager Walter Brown came to the dressing room to congratulate Don Mellor on scoring a goal in his first game with the team.

It was 1941 and Boston Olympics General Manager Walter Brown came to the dressing room to congratulate Don Mellor on scoring a goal in his first game with the team.

Don deflected the praise. “The puck was right in front of me on my stick, and all I had to do was tap it in, Mr. Brown.”

Brown answered, “But you were there, son, and that’s what counts.”

“I thought, that’s pretty nice, to know where to be,” Don said, almost 80 years later.

And that’s how you build one of Cranston’s and Rhode Island’s most notable hockey families. You know where to be.

A Kid on a Pond

“I was a young boy, 6 or 7 years old, and I was just attracted to skating,” Don said, on the eve of his 101st birthday. “It could be on a puddle, but just putting on a pair of skates was a thrill, I guess.

“I was a young boy, 6 or 7 years old, and I was just attracted to skating,” Don said, on the eve of his 101st birthday. “It could be on a puddle, but just putting on a pair of skates was a thrill, I guess.

“Then we started playing with a puck. Actually, it was a rubber heel. A rubber heel in those days was the closest thing to a puck. That would be on maybe a small pond. When I got a little older we skated on Blackamore Pond.”

Blackamore Pond was a few blocks from where the Mellors lived in Cranston.

“You work up a sweat, and you take your jacket off,” Don said. “You start off with one jacket here, and someone would put one there, then after a while you’ve got a goal. When the game was over, when the streetlights went on, you had to find your jacket somewhere in the pile.”

Pond hockey came with its own set of hazards, and those hazards built skills.

“Somebody would fire a puck through to open ice, and you’d have to, you know, hold some kid’s ankles and he’d get two sticks together to pull in the puck,” said Don’s son Tom. “And so you learned don’t fire the puck away, work it around and through the crease.”

“Somebody would fire a puck through to open ice, and you’d have to, you know, hold some kid’s ankles and he’d get two sticks together to pull in the puck,” said Don’s son Tom. “And so you learned don’t fire the puck away, work it around and through the crease.”

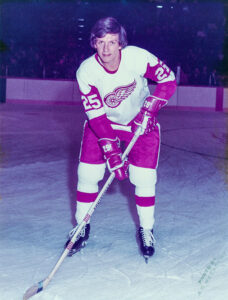

Tom learned those lessons well. He became a star at Boston College, played for the Silver Medal-winning U.S. Olympic Hockey Team in 1972 and was drafted by the Detroit Red Wings. He is a member of the Rhode Island Hockey Hall of Fame, Class of 2022.

The Paper Route

You’d expect the next chapter in this story to be Don’s stellar career playing schoolboy hockey. But you’d be wrong, because in 1929, the year the stock market crashed and the Great Depression began, Don started a paper route for the Providence Journal.

“The big thing that changed my life was having that paper route, believe it or not. I learned so much,” Don said. “With a paper route, you learn dedication. You learn patience. You don’t even think about the weather. You’re dealing with irate customers. You’re dealing with money. You learned to do what you were told. If a customer wanted the paper on the third floor you brought it to the third floor.”

Later on, Don’s four sons and one of his daughters would also work paper routes, learning the same lessons about hard work, dedication, and responsibility.

For Don, the paper route also meant no high school hockey.

“I learned so much from a paper route, but I had to give up trying out for the high school hockey team because I couldn’t go to the practices,” Don said. The practice times conflicted with his paper route.

But Don was about more than hockey. He also embraced baseball, softball, football and basketball.

“I had a friend on the hockey team, Bud Connolly,” Don said. “He was my idol, a little older than me, and he had an in with Ed Stebbins, the basketball coach, as he was the star. So he talked to Stebbins to have me try out for the basketball team, which I did, and I made the team. To be honest, I wasn’t that interested, but I was playing, and the hours were good for me, because I could practice.”

Bud Connolly was a star athlete at both Cranston High School and the University of Rhode Island, where he would become a two-sport Hall of Famer. Edward Stebbins Sr. was a teacher and coach of football, baseball, and basketball in Cranston for more than 40 years. As a football coach, Stebbins Sr. won 13 state championships, including one season when the team was unscored upon.

By the time Don entered his senior year, schedules had changed, and he tried out for the hockey team.

“I did make the hockey team, and I had a good year, and I played with some pretty good players,” he said. Don loved hockey so much that he pushed his graduation date from February to June 1939 so he could play.

Graduating to the Big Time

When Don finally graduated, he started work at Builders Iron Foundry. It was hot, grimy work. But Don still found the energy to play.

Amateur softball was big, and Don was a catcher for the Cranston Trojans, sponsored by a local ice cream shop. In 1940, the Trojans finished the year undefeated and earned a trip to the Amateur Softball Association Men’s Major Fast Pitch Nationals in Detroit. The following year, with Lindy’s Diner as sponsor, the team returned to the Nationals. But when the softball season ended and the cold weather came, it was back to hockey.

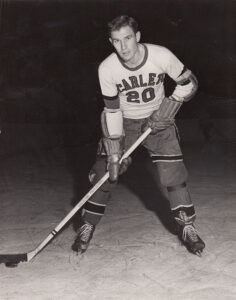

“I started playing amateur hockey around the neighborhood, and someone connected with our group knew someone in Boston. So we had a game in the Garden,” Don said. He was in the right place for his ability to shine. The Garden was home to the Boston Bruins and their farm team, the Boston Olympics. The Olympics were coached by Hago Harrington, who had recently retired from the Providence Reds.

“I started playing amateur hockey around the neighborhood, and someone connected with our group knew someone in Boston. So we had a game in the Garden,” Don said. He was in the right place for his ability to shine. The Garden was home to the Boston Bruins and their farm team, the Boston Olympics. The Olympics were coached by Hago Harrington, who had recently retired from the Providence Reds.

“We played the Olympics Juniors, and I came up with a good game, so I spoke to Hago Harrington and he said we’d like to take you to New York. It was getting big time,” Don said. “I went to New York, and I came up with another good game.”

He began practicing with the Olympics Juniors and, soon, with the Olympics senior team.

“So now I go up and play with the big team,” Don said. “And I was really into it. I was back and forth on the train (with the Olympics) and still working at Builders Iron Foundry.”

“It was exciting. Just having the equipment, just walking in the back door of the Garden,” Don said. “But I knew it wasn’t going to last.”

Balancing work at the foundry and playing with the Olympics was grueling.

“And finally I couldn’t make one trip, and Hago sent a telegram: Are you gonna play or not?”

Don decided that his job at the foundry and family came first. And he knew the draft was coming. So he ended his career with the Olympics after two seasons, 1941-42 and 1942-43.

“It was a whirlwind thing for me from not making the high school team to playing with the Boston Olympics,” Don said. “I mean, I have to stand up when I say that.”

Answering the Call

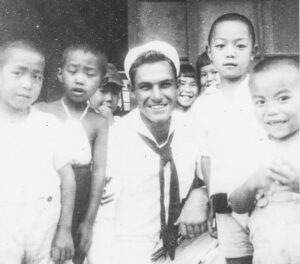

In 1943, Don thought his choice was clear: he could wait for the draft to assign him to a branch of the service, or he could enlist and make his own choice. He chose the Navy and became a Fire Controlman 2nd Class on the USS Hopewell DD 681, a Fletcher-class destroyer. The Fletcher was deployed to the South Pacific.

In 1943, Don thought his choice was clear: he could wait for the draft to assign him to a branch of the service, or he could enlist and make his own choice. He chose the Navy and became a Fire Controlman 2nd Class on the USS Hopewell DD 681, a Fletcher-class destroyer. The Fletcher was deployed to the South Pacific.

“I survived two big events in my life,” Don said. “The first thing was the Depression. That had a big effect on me, growing up, as a 13-year-old with no income, nothing given to you. You do the best you can.

“The next thing was the war. I can’t believe I survived it. I got to know people and learned how to judge people and figure out who you wanted to hang around with.”

When Don was discharged, he returned to his two loves.

The first love was Helen Phillips. The two had met when Don was working at the foundry. During the war, Helen served in the Coast Guard Women’s Reserve, known as SPARS. SPARS was an acronym for the Coast Guard motto: “Semper Paratus — Always Ready.” Don and Helen were married on Nov. 24, 1945.

The second love was sports. Don took up playing hockey and softball again.

He played defense for the R.I. Scarlets, an Atlantic Hockey League Senior Amateur team. Johnny Gagnon, who starred with the Montreal Canadiens and Providence Reds, was coach. Don also played for a local team sponsored by the Dunnes of Cranston with his good friends Ted Dooley and Al Bentley. Ted, son of Providence Reds founder and former AHL President Judge James E. Dooley, would go on to manage the Scarlets, and Al would later play goal for the Rhode Island Reds.

He played defense for the R.I. Scarlets, an Atlantic Hockey League Senior Amateur team. Johnny Gagnon, who starred with the Montreal Canadiens and Providence Reds, was coach. Don also played for a local team sponsored by the Dunnes of Cranston with his good friends Ted Dooley and Al Bentley. Ted, son of Providence Reds founder and former AHL President Judge James E. Dooley, would go on to manage the Scarlets, and Al would later play goal for the Rhode Island Reds.

“I was trying to play careful, and I got hurt. It happens when you play careful,” Don said.

It was a game in Boston, and Don was heading into the corner with an opponent. Don braced himself for a hit, and the player’s skate got him in the ankle. In the locker room after the game, the doctor decided the wound didn’t need stitching. But on the bus ride home, it started to hurt. So Don and Al went to the Rhode Island Auditorium to call on the Rhode Island Reds’ trainer, George Army.

“He took a little piece of leather out of the wound and wrapped it,” Don said. “He explained a puncture is worse than a cut because you never know what’s driven in.”

Don had just started working New England Telephone, and the wound meant he couldn’t climb telephone poles.

“My boss says, ‘You want to play hockey or work for the phone company?’ It was the easiest decision I ever made,” Don said. Just as he had done in high school, Don put work and responsibility first. By now, he and Helen also had a son: David, nicknamed Duke, born in 1946. Five other children followed: Tom in 1950, Donny in 1953; Joan in 1957; Paul in 1958; and Jackie in 1966.

“My boss says, ‘You want to play hockey or work for the phone company?’ It was the easiest decision I ever made,” Don said. Just as he had done in high school, Don put work and responsibility first. By now, he and Helen also had a son: David, nicknamed Duke, born in 1946. Five other children followed: Tom in 1950, Donny in 1953; Joan in 1957; Paul in 1958; and Jackie in 1966.

“So they took care of me, as far as letting me work in an office until I recovered,” Don said. “I put 35 years in with New England Telephone.”

Passionate About Hockey

Though he had stopped playing, Don remained passionate about hockey.

“Dad, so enthused about introducing us to the game, brought Tom and me to the (Boston) Garden on Jan. 19, 1958,” said Duke. “We were fortunate enough to see Willy O’Ree’s second NHL game in a home and home, as his debut was the night before in Montreal.”

O’Ree was the first Black player in the NHL. He played left wing for the Bruins, with center Don McKenney and right wing Jerry Toppazzini.

“We were also able to get Ralph Backstrom’s and Dickie Moore’s autographs as they carried their bags through the lobby,” Duke said.

While the Bruins were big, the AHL Rhode Island Reds were the home team, and Don and friend Dick McLaughlin went to games at the Auditorium twice a week. Don’s friend Ted Dooley had 12 box seats at center ice just below the press box and above the Reds bench.

“I remember dad putting his tie on every Sunday night,” said Tom Mellor. “We would plead with him to take us if we had our homework done, and we got to really know the Reds.”

Tom and Dick’s son, Rich, would became close friends and learn how to play the game from watching the Reds with their fathers.

One of the players they watched was Reds goaltender Harvey Bennett. Harvey played with the Boston Bruins, Boston Olympics, Hershey Bears and the Reds in his 15-year hockey career. He was the patriarch of Rhode Island’s First Family of Hockey. Four of his six sons — Curt, John, Harvey Jr. and Bill — would go on to play pro hockey.

Harvey also was one of Don’s good friends; they played softball together.

“The Bennett family was the best thing that ever happened for Rhode Island hockey,” Tom said. “Suddenly, now Harvey is getting the kids ice time at the Auditorium at Sunday noon for an hour. So for one dollar the kids loaded up.

“All the kids from the area would go, and there was Harvey Sr. skating around in goalie skates, and Chuck Scherza and Serge Boudreault would be skating around. Norm Calladine and Johnny Gagnon were there. So we’re out there skating with the pros.

“They’d teach us use your body, skate to where the puck is going to be, to move the puck ahead, don’t bunch up,” Tom said. “My brother Donnie was a goaltender, and he still says, ‘Little did I know back then that the guy with the goalie stick shooting pucks at me from the blue line was Eddie Giacomin, one of the greats.'”

Expanding Opportunity

Using his friendships to get kids icetime with the Reds was not enough for Don Mellor. Cranston had youth hockey, but it was limited to two Pee-Wee teams that played at the Ice Bowl, a tiny rink on the Cranston side of the Providence Shipyard.

Don’s son Duke remembers playing there as a teen.

“The thing about the Ice Bowl was, because it was so narrow, you didn’t have a lot of room to negotiate,” Duke said. “So our stick handling might be a little better just because of the fact that we played in a facility like that.”

To give more kids the chance to play and skate, Don helped found the Cranston League for Cranston’s Future. CLCF started in 1953 offering football, and it was based in a building at the city’s Budlong Pool. The pool was across the street from both Blackamore Pond, where Don skated as a child, and the Mellor home on Aqueduct Road.

To give more kids the chance to play and skate, Don helped found the Cranston League for Cranston’s Future. CLCF started in 1953 offering football, and it was based in a building at the city’s Budlong Pool. The pool was across the street from both Blackamore Pond, where Don skated as a child, and the Mellor home on Aqueduct Road.

With Don’s involvement, CLCF added hockey in 1955, and kids skated on the frozen pool. At night, the city turned on the pool lights.

“We would practice there in high school,” Duke said. “It was just a big square concrete pool where I told people going into the corners took on a whole new meaning.”

“All the kids were down there skating,” Tom said. “Dad was helping them, Dick McLaughlin was there, and Swede Erickson would come over from Warwick. The fathers were very involved.”

Ralph “Swede” Erickson had played for the R.I. Scarlets with Don.

Even with the pool pressed into service, there were more kids than that ice could accommodate. So Don persuaded the fire department to flood a large field behind the pool complex. Cranston kids called it the Aqueduct.

“We’d go down to the field every day,” Tom said. “We lived on Aqueduct Road, and then we moved three blocks up to Colonial Avenue, where it was a 10-minute walk. We were so fortunate.”

Playing at the Aqueduct came with its own set of lessons. The first ones weren’t necessarily about skating and passing.

One lesson was about hanging tough.

“When you had to walk to the pond, you know, it’s not like walking to the ballfield on a nice day,” Duke said. “And then you’re sitting there in the dark and taking your skates off and walking home cold and wet. I think that may say a little bit more about what young kids go through to play hockey, although today I’m sure there are guys in the National Hockey League who have never been on a pond.”

Another lesson was responsibility.

“We grew up with our parents telling us the right thing to do early and then letting us go out and doing it,” Tom said. “And if we didn’t do it right, we heard about it. Things like, ‘Be back before the streetlights come on, and if you’re not back, you’re not going to go to the game tonight’. So guess what, we came home before the streetlights came on.”

Don also worked to create opportunities for girls, helping to organize an hour of time for figure skating at the Ice Bowl on Friday nights. In those days, girls’ ice hockey didn’t exist.

“I remain close to Harvey Bennett Jr. to this day, and we talk about how it’s unbelievable how many kids came out of those programs,” Tom said. “Kids like Joey Cavanagh and Danny DeMichele and Ricky McLaughlin.”

And, of course, the Mellors.

Out of Cranston

After high school, Duke Mellor played high-level amateur hockey throughout the Northeast.

“We had this group, the Cranston Hockey Club,” Duke said. The club was an independent senior amateur squad that took on teams from Lewiston, VT., to Pittsfield, MA, to Washington, D.C.

“It was old-time hockey, and it was just so much fun,” Duke said. “We had a group of players that lived for this A lot of kids like myself who didn’t play in college but were pretty good players.”

But the best hockey would come a little later in life.

“I think probably the best league I played in was a league in the North Smithfield rink on Route 146,” Duke said. “That’s where guys like Serge Boudreault and Bobby Leduc played when they retired from professional hockey. They were still pretty young guys who just enjoyed playing hockey.”

For Don, playing better hockey also meant looking beyond Cranston.

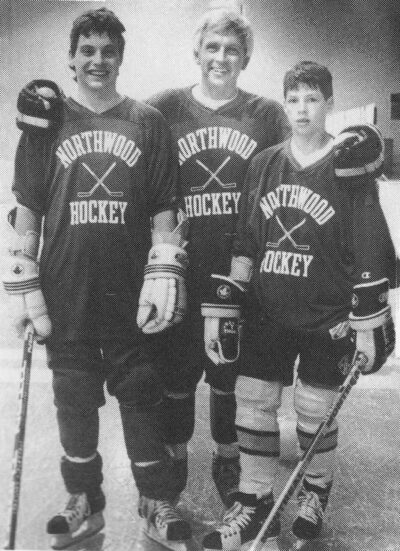

“Swede (Erickson) said Tom should be playing better hockey than the programs at CLCF or bantams,” Don said. “See if you can look into Northwood.”

The Northwood School is a preparatory school in Lake Placid, N.Y. Swede’s son, David, had gone there at the recommendation of George Menard. George, a member of another of Rhode Island’s great hockey families, was raised in Burrillville, played there and at Brown University, and was by now coaching the dominant St. Lawrence University Saints. David would go on to St. Lawrence after graduating Northwood.

The Northwood School is a preparatory school in Lake Placid, N.Y. Swede’s son, David, had gone there at the recommendation of George Menard. George, a member of another of Rhode Island’s great hockey families, was raised in Burrillville, played there and at Brown University, and was by now coaching the dominant St. Lawrence University Saints. David would go on to St. Lawrence after graduating Northwood.

“Let me tell you six schools I did not get accepted to,” said Tom, in his typical self-deprecating humor. “Deerfield, Andover, Choate, Harvard, Yale and Brown. Best things that ever happened.”

Best things, because they ushered the Mellors along the road to Northwood. It had an enormous impact on Tom’s game.

“Here I am, 14 years old, and I’m playing against guys like David Erickson, whose now a freshman at St. Lawrence,” Tom said. “I can remember a game where I challenged some big guy, and he knocks me down. I’m like a pancake and he’s over me, and David said, ‘Leave that kid alone; I know this kid.’

“But I’m playing against Middlebury, Hamilton, Clarkson — freshman teams rather than bantam hockey. And instead of playing 12 games we’re playing like 22 games. We’d go up to Canada. So my game is improving simply because I’m playing against these great players. And we’re getting ice at the Olympic Arena every day. And we get good coaching. Jim Fullerton. Charlie Holt. Sid Watson.

“So dad always says sheesh, mom and I felt very bad leaving you as a 14 year old,” Tom said. “I say, ‘Dad I can’t thank you enough.’ ”

Tom’s brother, Don, followed him up to Northwood and then spent 42 years there as a teacher. He was also Dean of Students for about 20 years and Assistant Headmaster for about four years. For much of his time there he was also the school counselor. His athletic passion moved to other heights; he is considered the Adirondacks’ premier expert in rock and ice climbing.

Tom’s performance at Northwood opened the route to Boston College.

As a freshman in 1968-69, Tom scored nine goals and 19 points in a 17-game season. As a sophomore, he tallied 21 goals and 44 points in 26 games. He followed that up with 40 points in 25 games the following year. Tom also played 18 games for the U.S. National Team that season.

As a freshman in 1968-69, Tom scored nine goals and 19 points in a 17-game season. As a sophomore, he tallied 21 goals and 44 points in 26 games. He followed that up with 40 points in 25 games the following year. Tom also played 18 games for the U.S. National Team that season.

Then came 1972, and the Olympics in Sapporo, Japan.

These were the days before professionals played for the U.S. team. European squads, however, made no distinction between professionals and amateurs and were loaded with talent and experience.

Tom played defense for the Olympic team; the goalie was Tim Regan. Tim, a 3-time LaSalle All-Stater, played college hockey for Boston University, leading them to 2 NCAA titles, and he would be drafted by the Buffalo Sabres. He was also one of the Cranston kids.

“Tim and I were always teammates when we young,” Tom said. “My father would pick up Tim, then drive the two of us to practice.”

The U.S. team, expected to finish fifth, won the Silver medal.

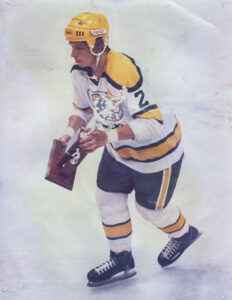

Tom returned to Boston College for his senior year in 1972-73, scoring six goals and leading the nation with 45 assists in 30 games. He then played for the Detroit Red Wings, which had selected him in the fifth round in the 1970 Amateur Draft. He later played in the AHL with the Virginia Wings; the British League in London; the IHL with the Toledo Goaldiggers, and the Swedish Elite League with Vastra Frolunda. He ended his professional career by winning the James Gatschene Memorial Trophy, given to the Most Valuable Player in the IHL, and the Governors’ Trophy, awarded to the league’s Outstanding Defenseman.

Tom returned to Boston College for his senior year in 1972-73, scoring six goals and leading the nation with 45 assists in 30 games. He then played for the Detroit Red Wings, which had selected him in the fifth round in the 1970 Amateur Draft. He later played in the AHL with the Virginia Wings; the British League in London; the IHL with the Toledo Goaldiggers, and the Swedish Elite League with Vastra Frolunda. He ended his professional career by winning the James Gatschene Memorial Trophy, given to the Most Valuable Player in the IHL, and the Governors’ Trophy, awarded to the league’s Outstanding Defenseman.

“He gave me one thrill after another,” Don said. “I can remember a lot of goals he scored. And I can remember a lot he didn’t score. But it was always a great thrill. And I had four boys, and I’m so proud of all of them.”

“He gave me one thrill after another,” Don said. “I can remember a lot of goals he scored. And I can remember a lot he didn’t score. But it was always a great thrill. And I had four boys, and I’m so proud of all of them.”

Back to That Kid on the Pond

So that’s how you build a hockey family. You move to where the opportunity is going to be — not where it is. You team up with good people. You teach the value of dedication and patience and sacrifice.

And you love skating.

“Dad was such a beautiful skater,” Tom said. “I remember the last time my dad skated. I was going down to New York City on business, a hockey-related thing, and I decided to fly down with my son, who was about 15, and my dad.”

“We decided to go to Rockefeller Center. And we don’t have skates, but they rent figure skates. Now my son’s a hockey player. And the figure skates got the teeth on the front of the blade, right? So I said, I’m just sitting this baby out.

“So, I’m standing along the boards. And dad has a blazer on, and he’s got figure skates, and he is skating around, with his hands behind his back, he understands, right? And he’s just skating around, and he wasn’t a young man, 75 years old or something like that, and my son goes to dig in, and he gives up, and finally we’re just standing at the boards, watching my dad.”

By Mike Bailey