If you’re a fan of hockey in Rhode Island, you no doubt know a lot about the Bennetts.

Here’s something you probably don’t know:

In 1980, two of them — Curt and Harvey Jr., their NHL careers completed — went to the Far East and played two seasons of professional hockey in Japan.

See? Told you.

The story of the Bennett family is well-known. Harvey Sr. was the Reds’ regular goalie in the late ’40s and 1950s (backstopping them to a Calder Cup championship in 1949), and settled permanently in Rhode Island soon after arriving in Providence. Mark Divver, a member of the R.I. Hockey Hall of Fame’s board of directors, made the case in the pages of the Providence Journal that Harvey Sr., a charter member of the Hall, “put R.I. hockey on the map“, and it’s hard to argue. Click the link to get a full appreciation of how Harvey Bennett helped hockey grow and prosper here.

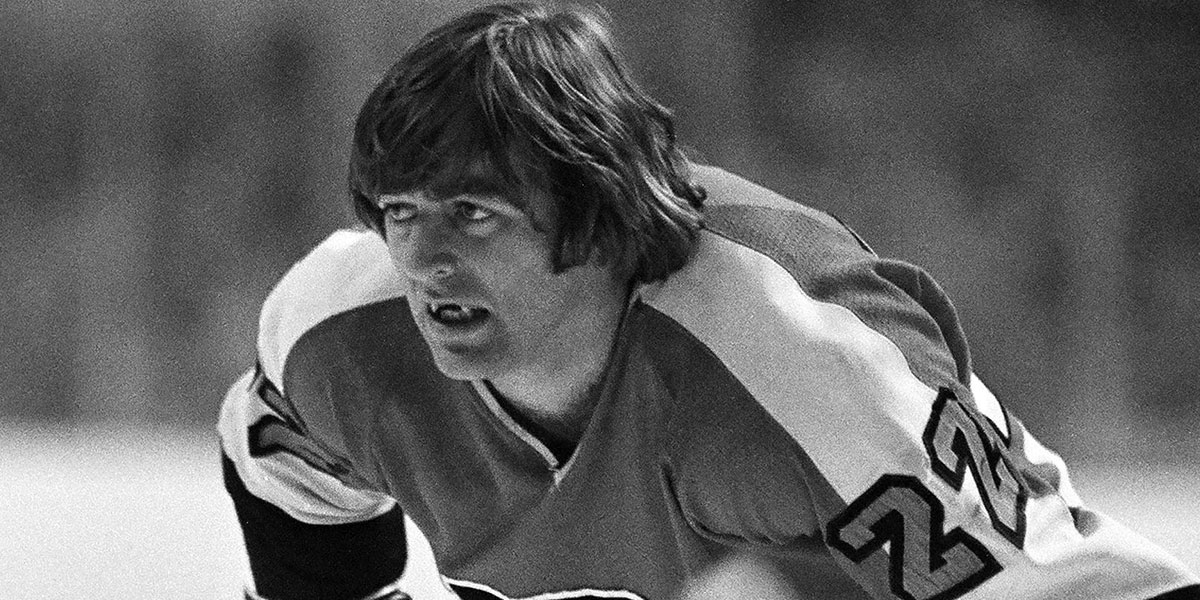

Curt was the first — and one of the most accomplished — to march down the path that was opened by his father. A brilliant career at Cranston East, where he was the star of perhaps the greatest high school team in the state’s history: The 1966 Thunderbolts. (And yes, I’m well aware of Bill Belisle’s superb Mount squads.) An All-American at Brown University. A 10-year NHL career, in which he made two All-Star teams and became the first U.S.-developed player to score 30 goals in a season . . . something he did twice.

A National Honor Society student who was named Rhode Island’s top scholar-athlete by the Journal as a high school senior, Curt was no prototypical rink rat. He had his eyes open to the world beyond.

“I think I enjoyed the international games the most . . . ” he said in a 2007 interview with greatesthockeylegends.com. “I played for Team USA in the Canada Cup and in the World Championships in Prague in 1978 and Moscow in 1979 . . . The international flavor of hockey is what I most remember.”

So it was natural, then, that Curt and one of his brothers, Harvey Jr. — who played five seasons in the NHL himself, including one (1978-79) with Curt in St. Louis — would head to Japan for what was, to say the least, a totally new hockey experience.

For one thing, the 6-foot-3, 195-pound Curt and the 6-4, 215-pound Harvey towered over their new teammates.

“The [Japanese] players probably weigh an average of about 50 pounds less and [are] probably about six inches shorter,” Harvey said in a televised interview that Curt conducted for a station in Atlanta. (Curt’s greatest years in the NHL were spent with the then-Atlanta Flames, and he sent a tape back to one of the stations soon after he and Harvey arrived.)

“I’ll tell you, they’re really scared of Harvey,” Curt said with a laugh on the tape. “He’s got that beard, too. Not many of the players have beards. And when he takes his teeth out, he’s pretty imposing. Our first day of practice, Harvey checked one of the players and knocked him right out of the rink!”

“I’ll tell you, they’re really scared of Harvey,” Curt said with a laugh on the tape. “He’s got that beard, too. Not many of the players have beards. And when he takes his teeth out, he’s pretty imposing. Our first day of practice, Harvey checked one of the players and knocked him right out of the rink!”

But it was more than just size. The differences in North American and Japanese cultures were reflected in how they approached the game. Curt chronicled them in a series of videos he made for ESPN — which was in its infancy then — and other American TV stations in NHL markets. The videos survive to this day on YouTube, and are fascinating to watch. In Curt’s words:

— “The team lives together in a clubhouse during the season. Even the married players live in the clubhouse, apart from their families.”

— “[The Japanese stress] the group over the individual. The team eats, sleeps, meets and exercises together.”

— “Each player sharpens his own skates, something very few professional players (in North America) do on their own.”

— “Since all six [Japanese professional] teams play in one city at a time, we dress in our clubhouse and walk (through the city) to the game.”

— “Politeness is important, and the team salutes the fans before the game. They salute the opposing team, then the captains approach the referees together to bow their respect.”

— “A Japanese referee wields more authority and respect than a North American. Criticism is impolite, and rarely do the players or the audience voice disapproval over his decision. If they do, he shows no patience.”

— “The fans yell, ‘Ganbattekudasai,’ or ‘Do your best, please.’ Jeers and catcalls are considered bad manners, and are seldom heard.”

— “Japanese culture discourages outward displays of emotion. If tempers erupt (during the game), it’s usually between the foreigners . . . But Japanese players quickly restore decorum.” (Harvey, who amassed 347 penalty minutes in 266 NHL games, was one of the foreigners whose temper sometimes erupted. In one of the videos, he noted a bit whimsically: “If there’s a rough play in the corner, each guy will bow to each other and say ‘Sumimasen’, which means ‘Excuse me.'”)

And remember, back at home this was the era of the Broad Street Bullies and the Big Bad Bruins. The fans in places such as Madison Square Garden and the Montreal Forum — who didn’t consider jeers and catcalls to be bad manners — rarely chanted, “Do your best, please.” Yes, this was a far cry from what the Bennetts were used to.

The natural ending to this tale would be that the Bennett brothers, like their father years earlier in Rhode Island, blazed a trail for Japanese hockey that resulted in growth for the sport in that country and an influx of native-born Japanese into the North American professional ranks. Alas, that was not to be.

After two years in Nikko, Japan playing for Furukawa Denko — Curt, who was 32 when he arrived there in 1980, was player/coach; Harvey, then 28, was simply a player — the Bennetts returned to the States. Both became successful businessmen: Curt in Atlanta and then Hawaii, where he deals in real estate, and Harvey in Rhode Island as president of Wendy’s Providence Co-op.

Curt also had a hand in getting the NHL back into Atlanta in the 1990s, though the expansion Thrashers eventually suffered the same fate as the Flames. Curt’s Flames moved to Calgary in ’80, the same year he went to Japan (“The media talk in Atlanta was, ‘Hell, if Curt can’t play for the Flames anymore we’re going to get rid of them,’ ” Curt joked in his greatesthockeylegends.com interview), and the Thrashers were sold and moved to Winnipeg, where they became the new incarnation of the Jets, in 2011.

The pro game in Japan never expanded beyond the six Japan Ice Hockey League teams in existence when the Bennetts were there, and the JIHL folded in 2004. There are now four pro teams left in Japan, including one in Nikko, and they participate in the Asia League Ice Hockey organization with teams from China and South Korea.

Only one Japanese native has ever played in the NHL: Yutaka Fukufuji, a goaltender who appeared in four games for the Los Angeles Kings in 2006-07. Others who you might suspect are Japanese — Edmonton’s Kailer Yamamoto, ex-Carolina Hurricane and Florida Panther Jon Matsumoto, the now-retired Kariya brothers — are either Canadian or American, with partial Japanese ancestry.

None of this, obviously, is any reflection on Curt or Harvey. Fact is, simple genetics may be the biggest factor why there’s no virtually Japanese presence in modern North American hockey. Harvey noted how small the Japanese players were upon his arrival in 1980, and it’s still true 40 years later. The average adult male in Japan is 5-foot-6 and 138 pounds. In the NHL, the average player is 6-1, 199.

What Curt and Harvey Bennett’s two years in Japan did do — through Curt’s videos — was shine a light on how the sport is played on a different stage, and how the game adapts to the circumstances that surround it. It’s still the same game, and it’s still a super game, even when it’s approached in a vastly unfamiliar manner.

Not having a storybook ending doesn’t mean it’s not a great story.

Posted by Art Martone