From youth leagues to the pros, the goaltender’s facemask is standard and required equipment. Younger generations might be surprised to know that it hasn’t always been that way.

Prior to the 1950’s, no self-respecting goalie, let alone hockey player, would be caught hiding behind a mask. While, from time to time, there was the occasional goaltender who wore some form of protective face gear for a short time, it would not be until 1959 that a professional goalie would wear a mask full time. It was Jacques Plante of the Montreal Canadiens.

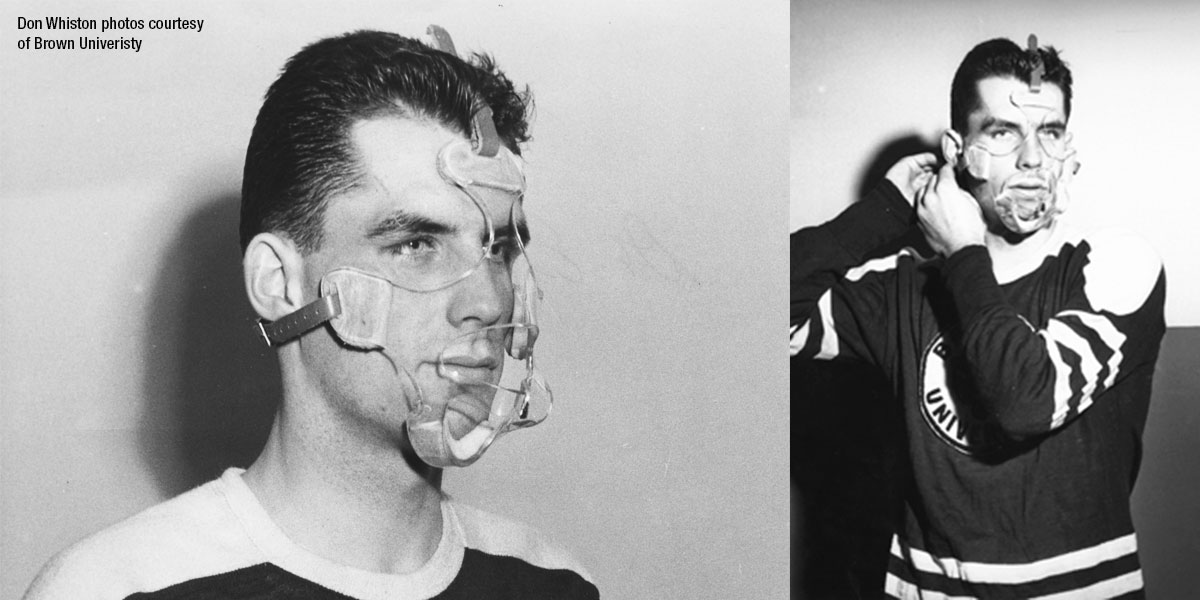

Yet it was in 1949 that a former Brown University hockey player and then doctor for Brown’s athletic teams, Dr. G. Edward Crane, received national attention when he designed a full-time plastic facemask for Don Whiston ’51, the Bears’ then fine sophomore goalie.

Yet it was in 1949 that a former Brown University hockey player and then doctor for Brown’s athletic teams, Dr. G. Edward Crane, received national attention when he designed a full-time plastic facemask for Don Whiston ’51, the Bears’ then fine sophomore goalie.

That 1949 facemask came about as a result of action in a game at Princeton, when a puck struck the future All-American flush in the mouth, bending his bottom teeth back into his tongue. Thinking quickly and fashioning some stainless steel wire from the Princeton infirmary, Dr. Crane wired the teeth back in place. Whiston, a great competitor, was back in the nets the next night at Army, wearing a West Point football helmet and face guard.

“Whiston didn’t want to wear anything that would block his vision,” Dr. Crane recalled. “But the boy had suffered a serious injury and it was necessary to come up with something that would protect him from having another puck hit him in the same area.

“There was an outfit in Brooklyn that had been experimenting with football face masks made of plastic. I designed a special mask for Whiston, sent it to this firm, and they produced it for me. The mask covered Whiston’s cheekbones, nose, mouth, and chin but left the eyes free. He wore that contraption through the rest of his college career, made All-American, became a USA Olympian, and received a lot of publicity as the first college goalie in the country to don a facemask.” That facemask became the forerunner of the present day full facemask worn by every goaltender today.

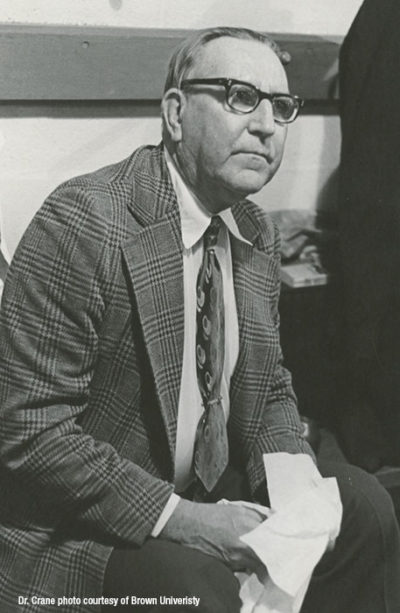

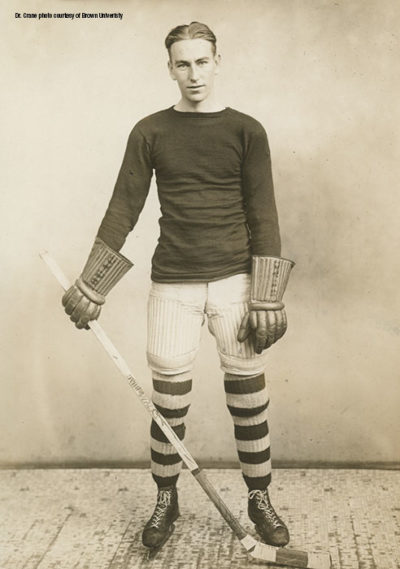

George Edward “Eddie” Crane, M.D. was born on January 23, 1910, in Providence, RI. He attended Classical High School and graduated in 1927. He was as superb a schoolboy athlete as he was a star athlete at Brown, earning seven letters in hockey, baseball, and soccer with the Bears. In his senior season he was the leading scorer on his hockey team that won nine of 10 games and was captain of the baseball team.

Graduating from Tufts Medical School in 1935, Crane did his internship at Pawtucket Memorial Hospital and then became a member of the orthopedic and fracture staff at Rhode Island Hospital.

During the war, he served as a captain with the 243rd Coast Artillery. He put on the baseball uniform once more during that time, coaching the Fort Adams (RI) team to the championship of the 1st Army Corps Area. The championship game was played at Fenway Park as a preliminary to a Boston Red Sox game with the St. Louis Browns.

“There were about 5,500 fans in the stands that day,” Dr. Crane recalled. “I’ve always liked to think that most of them came to see our game, not to watch the St. Louis Browns.”

“There were about 5,500 fans in the stands that day,” Dr. Crane recalled. “I’ve always liked to think that most of them came to see our game, not to watch the St. Louis Browns.”

In 1946, Dr. Crane became the team physician and athletic surgeon for Brown. Considered one of the top orthopedic surgeons in the East, he covered well over a thousand Brown athletic contests during his career. He opened his private practice at nearby 185 Angell St., so he could be as close as possible at all times to the University and “his” players.

Dr. Crane’s effect on the game can still be felt today. No one cared more and did more to prevent injuries to his players. He was, in fact, fifty years or more ahead of his time when it came to safety. His guiding philosophy was that if an athlete was injured, they did not play. In 1950, he was directly responsible for convincing the NCAA Rules Committee to require all collegiate hockey players to wear a helmet. He would be thrilled to see that USA Hockey now even requires all coaches to wear a helmet while on the ice.

During his lifetime, he was awarded an honorary membership into the National Athletic Trainers Association, the equivalent of that organization’s Hall of Fame. It was based on his passion for creating state-of-the-art sports medicine. But Dr. Crane did not follow the latest cutting-edge science and medicine. He created it with his passion for head and face protection. Without his contribution to head protection in hockey there is the very real possibility that the game would not exist today.

Dr. Crane is enshrined in the Helms Hall of Fame and the Brown Athletic Hall of Fame. He was also inducted into the Rhode Island Football Coaches’ Association Hall of Fame and provided medical services to many high school football players, free of charge, during his career.

Dr. Crane died on July 12, 1981 in Narragansett, RI.

Posted by RIHHOF