From youth leagues through college in the late fifties and sixties, Woonsocket’s Roger G. Guillemette was one of New England’s most highly accomplished hockey talents.

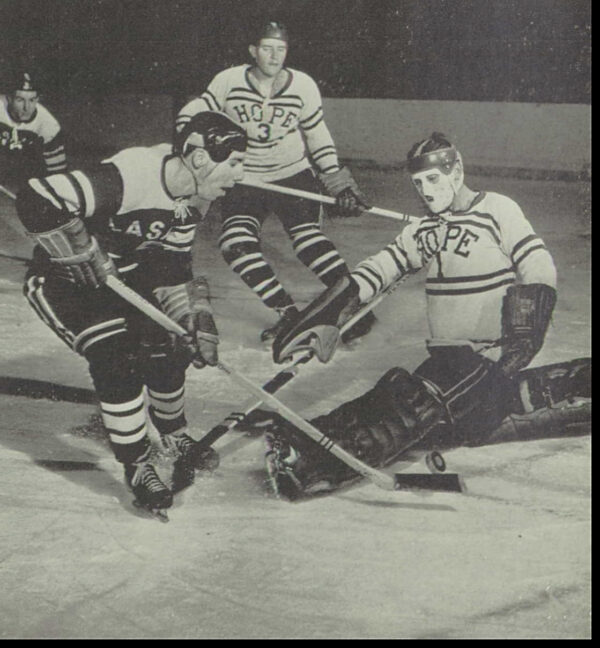

A super-quick forward, Guillemette enrolled at nearby Mount St. Charles before transferring to LaSalle Academy for his sophomore year. The All-State forward would go on to lead the Rams in scoring for three seasons, helping them to two league titles and earning MVP honors when the team captured the New England championship here in Providence in 1961.

A super-quick forward, Guillemette enrolled at nearby Mount St. Charles before transferring to LaSalle Academy for his sophomore year. The All-State forward would go on to lead the Rams in scoring for three seasons, helping them to two league titles and earning MVP honors when the team captured the New England championship here in Providence in 1961.

When he graduated, 15 colleges came calling before he chose Norwich University. As team captain, he led Norwich to two ECAC crowns, was the school’s top scorer and MVP, and twice earned All-East honors.

But none of that may have been possible if not for his father.

His father, Roger J. Guillemette, was Canadian born. He arrived in Woonsocket as a young boy. “My grandfather was a farmer from Saint-Hyacinthe in Quebec,” young Roger recounts, “and his farm wasn’t paying the bills. So, like so many other French-Canadians who populated the region at the time, he was lured here for the jobs available in the textile mills.

“My father wasn’t highly educated. He had to leave school after the 8th grade but he was smart and inventive,” he proudly continued. “He became a master carpenter and he could build anything. He particularly loved hockey and talking to me and my younger brother and sister about the Richard brothers, Jacques Plante, Jean Beliveau and all of his Canadiens hockey heroes.”

So, naturally, Roger Sr. put his children on skates at an early age. “I think I was five when we started skating on the local ponds together,” Roger recalled. “We skated so much, we pretty much wore the edges off our blades. Dad knew we needed good edges to be good skaters.” He quipped, “When he would drive me to the packed public skating sessions in Worcester or Providence, he would tell me to find the best skater and skate behind him for a fast, clear path.”

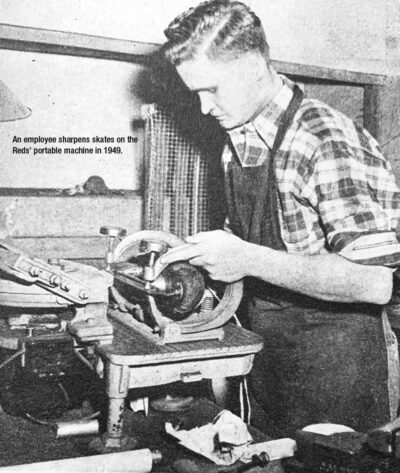

Mr. Guillemette was acquainted with Norman Rosa, the superintendent at the RI Auditorium and nephew of RI Reds owner Lou Pieri. One day he asked Norm where he might buy a machine to sharpen skates. He was surprised when Norm said there was an old portable skate sharpener gathering dust at the Arena.

The machine may have been the same that the great Reds and Montreal Canadiens defenseman, Art Leseiur, bought to sharpen his own skates and, eventually, those of his teammates but left behind when he was suddenly drafted into the Army in 1941.

“My father bought the machine and we never had dull blades again,” Roger says. “Soon, out of our garage, he was sharpening blades for everyone around, including friends, Mount St. Charles, Woonsocket High and the Woonsocket Elks, the first youth team in the area, which dad organized in 1956.”

As time passed, it became apparent that the old portable machine could no longer stand up to the high volume of grinding required of it, so Roger Sr. set out to build a new and more substantial one.

As time passed, it became apparent that the old portable machine could no longer stand up to the high volume of grinding required of it, so Roger Sr. set out to build a new and more substantial one.

“My father knew exactly what to do,” says his son. “Using the existing machine as his model, he built a bigger and better version – every detail and to exact scale – out of wood. He brought the model template to a foundry, which made a mold of the components in sand and then cast them in metal. The castings were then finished in a machine shop.”

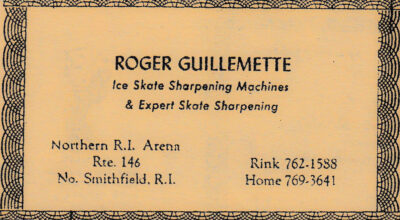

Word of Mr. Guillemette’s creation got around. His skate sharpening business was booming and, in the early 70’s, he moved his business to the newly opened North Smithfield rink, where he sharpened hockey and figure skates for the next 15 years.

There, according to his son, Roger Sr. became sought after for his ability to not only grind the perfect edge on the blades but also the perfect custom “rocker”, or blade profile. Except, perhaps, for goalie skates, hockey blades are not perfectly flat. They have a curvature from heel to toe.

“Anyone who sharpens skates for a while can tell just by looking at the blades whether the wearer plays forward or defense,” Mr. Guillemette would say. “If a player wants more maneuverability, a good sharpener can give it to them.” The more blade that touches the ice enhances speed and stability. Less blade-to-ice contact increases maneuverability and acceleration. At the pro level, the rockers, which typically range from two to four inches in length, are as unique as the player’s fingerprints.

Players and trainers agree that as important as good boots are, they are secondary to the blades. Good skates have good blades and they last a long time. The cheaper the skate, the faster they lose their edge and the more often they need sharpening.

Tommy Woodcock knew that intimately. In the late 60’s, Woodcock sharpened the skates of the RI Reds. The protégé of Reds legendary trainer, George Army, Tommy would go on to a Hall of Fame career as an NHL trainer. But now he had been hired as trainer of Jim Fullerton’s Brown University hockey team. He needed a skate-sharpening machine and Roger Sr. was the man to see.

At first reluctant, the busy Mr. Guillemette made the machine for a grateful Woodcock. But, as fate would have it, soon thereafter, Tommy would be moving again, off to the head trainer’s position with the St. Louis Blues. Once again, he came calling. This time with Brown coach, Jim Fullerton, by his side.

Tom needed yet another machine to take with him to St. Louis. Coach Fullerton was there to recruit young Roger. One of their wishes came true. The machine would be built.

Tom asked not for one machine, but three, including one for his younger brother Rollie, who was about to open a skate shop at the new Dudley Richards rink in East Providence. It was the Bobby Orr era. Hockey was booming and rinks were being built and planned in other parts of the region, as well. Since he had agreed on making three, “Why not six” the young Roger recalls his father figuring. There would be need and the price per machine would be considerably less.

The machines were all spoken for before they were even finished – off to Tommy and to the Dudley Richards, Schneider, Mid-State, North Providence, and Milford, MA arenas. More would follow.

“This was the time my father took advantage of the relationships he had cultivated with the vendors he worked with over the years,” Roger noted. “Like today’s digital printers need ink refills, from time to time the skate sharpeners required replacement grinding wheels and the industrial diamonds needed to dress and maintain their precision grinding condition. Dad provided them.”

“This was the time my father took advantage of the relationships he had cultivated with the vendors he worked with over the years,” Roger noted. “Like today’s digital printers need ink refills, from time to time the skate sharpeners required replacement grinding wheels and the industrial diamonds needed to dress and maintain their precision grinding condition. Dad provided them.”

Another component required for the machines were the skate holders – a critical piece of equipment necessary to achieve a perfect hollow along the entire length of the blade. These, too, could not be store-bought.

“My father tracked down the name of a man who tooled and made his skate holder. He lived in Toronto. Unlike today, where business could be conducted over the phone or via email, Mr. Guillemette hopped into his car and journeyed to Canada to meet the man in person.

When he asked to purchase the rights to reproduce the skate holder, the man refused. Instead, he offered something better. He would give Mr. Guillemette the patent rights for free, explaining that at his age he was no longer interested in the work but wanted his creation to continue in use. An appreciative and cautious Roger engaged a lawyer to draft formal paperwork to legally convey the rights to the patent. Then, in the same way he set about building his skate sharpening machines, he forged and machined the companion skate holders.

The younger Roger reminisces. “It’s hard to imagine how many pairs of skates were sharpened on my father’s machines over all these years, or how many hockey and figure skaters played or performed on the edge they produced. Looking back, we probably missed out on a more lucrative business opportunity if we had more business savvy at the time,” he laments.

The younger Roger reminisces. “It’s hard to imagine how many pairs of skates were sharpened on my father’s machines over all these years, or how many hockey and figure skaters played or performed on the edge they produced. Looking back, we probably missed out on a more lucrative business opportunity if we had more business savvy at the time,” he laments.

Roger, who followed his brilliant playing days with impressive head coaching stops at Bellingham High School, Bishop Hendricken, and Roger Williams College, estimates his father built 20 or so custom machines – his name proudly engraved on each – and most, if not all, still grinding away. Three went to NHL organizations – the St. Louis Blues, Hartford Whalers, and the short-lived Kansas City Scouts, which became the Colorado Rockies.

When Mr. Guillemette passed at age 76 in 1992, he left three machines to his children. Roger’s found its way to Mount St. Charles’ where it is still in use at Adelard Arena. Sister Michelle sold hers to a local player, Chris Decelles. And Bob’s is now owned by longtime family friend and former Reds favorite and WHA player/coach Bob Leduc, who uses it for family, including grandchildren who appear to be a chip off the old block.

Treasures all and still capable of producing that perfect edge.

By RIHHOF