Anthony Venditti became famous in automotive circles, not only here in Rhode Island but in a good part of the nation. Known as the “Godfather” of stock car racing in New England, his almost single-handed creation of the Seekonk Speedway and the innovations he introduced to the sport there made him one of the early architects of today’s NASCAR.

He is equally important in the annals of RI hockey for his creation of “Iceland”, the first commercially successful outdoor ice skating rink in the region, which he began building in the early 1950’s on the site of his family’s homestead in front of his raceway on Fall River Avenue in Seekonk. This is the story of how Iceland was born.

Domenecio Anthony Venditti, the son of Italian immigrants, was born in Providence in 1917. His family operated a poultry business in the city’s popular Federal Hill neighborhood, not far from the tenement building where the family resided. Anthony attended grade school but was, for the most part, self-educated. He was blessed with an old-world work ethic, plus intellect, ambition, and ingenuity. In the words of his daughter, Adrienne, “At age five he learned how to properly mix cement while helping to build our grandmother’s house. Eventually, he could build anything. And if he didn’t get it right the first time, he kept at it until he got it the way he wanted.”

Domenecio Anthony Venditti, the son of Italian immigrants, was born in Providence in 1917. His family operated a poultry business in the city’s popular Federal Hill neighborhood, not far from the tenement building where the family resided. Anthony attended grade school but was, for the most part, self-educated. He was blessed with an old-world work ethic, plus intellect, ambition, and ingenuity. In the words of his daughter, Adrienne, “At age five he learned how to properly mix cement while helping to build our grandmother’s house. Eventually, he could build anything. And if he didn’t get it right the first time, he kept at it until he got it the way he wanted.”

In his teens, Anthony became the breadwinner for his family, raising the chickens, dressing them, and delivering them to the family’s Federal Hill storefront. On weekends, he would drive them to the markets in New York City wearing his finest suit as a reflection of the quality of his product. It was hard, demanding and, frankly, dirty work that he would come to dislike as the years passed.

Anthony’s youngest child, Anne-Marie, is fond of saying that ice was at the core of her family. Her father met her mother, Irene, while ice skating. Irene’s father was in the ice harvesting business. Before there were refrigerators there were ice boxes and Irene’s father filled them, cutting and harvesting ice from local ponds and storing the blocks in straw to preserve them in Seekonk’s Old Grist Mill, now a popular restaurant.

In time, the Venditti family had saved enough money to move. They pooled their funds with other family members and purchased a 20-acre farm with a large house and barn on Fall River Avenue in Seekonk. At one point, 17 family members lived in the large house. Meanwhile, the family raised their chickens in the adjacent barn while Anthony was getting bitten by the auto racing bug – midget car racing, to be exact.

He dreamed of his own racetrack – and he needed only to look out his back window to see where he would build it. But first there was a problem to solve.

The land was sloped and mostly peat and topsoil – gardener’s gold but not the stable ground you would build a large structure on. So, Anthony struck a deal with the Clarke Quarry on Seekonk’s nearby Commerce Way. Clarke would remove the valuable landscaping material and replace it with gravel and remnant quarry stone. Eventually, the land was solidified and elevated 50 feet above its original level. Now, at age 25, Anthony embarked on his dream to build his racetrack. Along with his sons, he put his back, his experience and his ingenuity into every aspect of the construction.

The Seekonk Speedway opened on Memorial Day in 1946. It enjoyed an incredible first year. Throngs filled the oval over the first years of racing with his Demolition Derby events becoming the biggest draws. The success allowed the Venditti’s to eventually abandon the poultry business and continue to expand and improve what would become a “coliseum” track, an oval completely surrounded with seating. The entire family was involved in the operations. “We lived racing twenty-four hours a day,” Adrienne recalls.

When winter arrived, the track was quiet and taxes had to be paid. One day, Anthony and Irene had a family meeting, one of the few the family ever had. Adrienne explained, “We were so busy with all of my father’s projects, we never had time to meet.”

At the family gathering, Anthony explained that they needed a year-round income. That would mean finding another way to make money to support the family – a new venture to generate revenue besides the seasonal racing income with its attendant fear of a bad year at the box office. He said to his wife, Irene, and kids, “What do you think about opening an ice rink?” The children and Irene, a speed skater and racer in her youth, enthusiastically approved, all the while knowing they would have a lot of work ahead of them.

With the help of his two young sons, Francis and “Little” Anthony, the elder Venditti designed and constructed the entire skating complex, which was built right next to the family house and barn.

At the start of construction of the machine room, one cinderblock wall had been completed when a hurricane was forecast. At the height of the storm, with arms outstretched, Anthony and his family locked arms, leaning on the wall with other reinforcements as the wind raged against it. Miraculously, it held.

With the building complete, the engineering and installation of the ice-making machinery began. It was a complicated and monumental task. The gigantic turbines and combine engines were bought second-hand from an East Providence ice plant located under the Washington Bridge. Anthony fashioned all of the connections and gauges, color-coding them for safety and ease of operation.

He poured the concrete base and personally welded, connected and laid 5 miles of pipe (he insisted on copper over iron or steel), which he then sandwiched with another layer of proper concrete. Two silo stacks were installed to store the ammonia brine that would run through the piping to make the ice. Youngest daughter, Anne-Marie, who was little more than a toddler when the rink opened, recalls that the machine room was off limits to the children. “It was thick with the noxious aroma of ammonia,” she lamented. “My father developed emphysema, which was later attributed to inhaling those fumes.”

He poured the concrete base and personally welded, connected and laid 5 miles of pipe (he insisted on copper over iron or steel), which he then sandwiched with another layer of proper concrete. Two silo stacks were installed to store the ammonia brine that would run through the piping to make the ice. Youngest daughter, Anne-Marie, who was little more than a toddler when the rink opened, recalls that the machine room was off limits to the children. “It was thick with the noxious aroma of ammonia,” she lamented. “My father developed emphysema, which was later attributed to inhaling those fumes.”

The barn, once populated end to end with hens and chickens, became the welcoming station to Iceland. It was totally remodeled complete with ticket counter, a changing/warming room, an observation space, refreshment concession, and a skate rental and sharpening service. A small bank of bleacher seats was erected.

The final brilliant addition to the complex was outdoor lighting, also a first for the region. Over Iceland’s history, legions of local skaters would play under them into the wee hours of the morning.

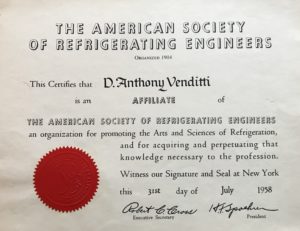

The standard-sized rink officially opened in 1952 and was considered complete in 1954. For his remarkable accomplishment, Anthony was presented with an honorary degree from the American Society of Refrigeration Engineering.

The standard-sized rink officially opened in 1952 and was considered complete in 1954. For his remarkable accomplishment, Anthony was presented with an honorary degree from the American Society of Refrigeration Engineering.

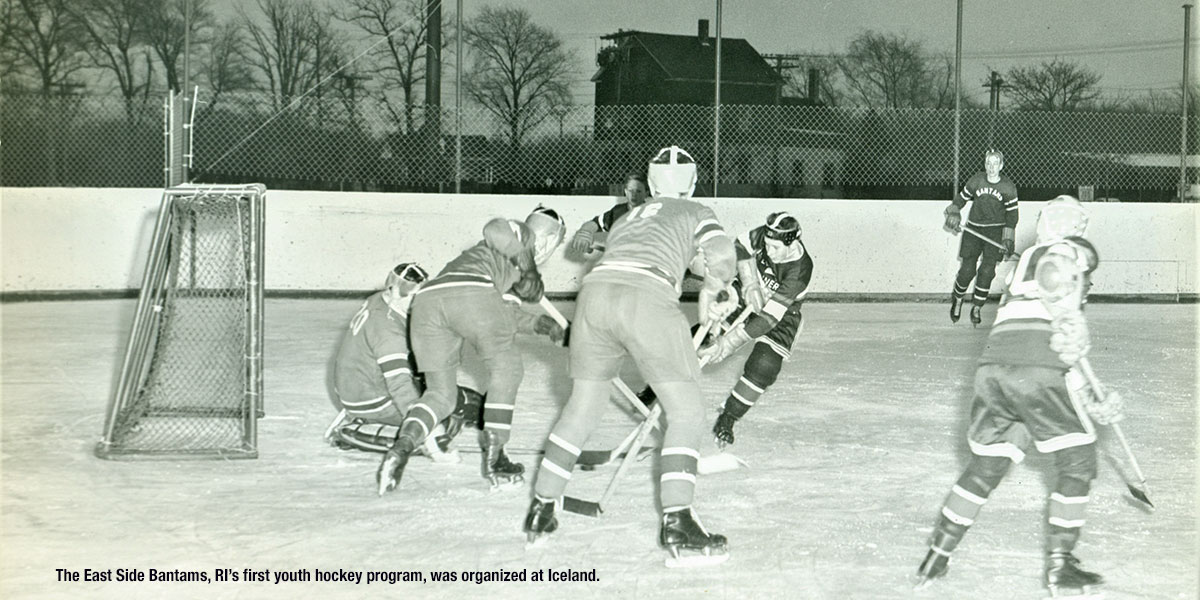

The rink was immediately popular, busy seven days a week weather permitting. It hosted public skating, instructional classes, and several hockey leagues, which it promoted the formation of prep school, amateur and the very earliest of the area’s youth hockey programs. One of those pioneer programs was the East Side Bantams formed by former Brown hockey great, Foster “Pete” Davis. With the help of other fathers and he as coach, Pete organized the team with players ranging from 10 to 14 years of age. In 1961 the team moved from Iceland to Brown’s Meehan Auditorium, which Davis championed the construction of and where they changed their name to the Brown Cubs.

Iceland became the home of a number of regional schools, including East Providence High, Providence Country Day and Moses Brown. When the RI Auditorium wasn’t available, Tom Eccleston often practiced his Providence College Friars at the rink. It was also a haven for figure skaters, which was especially important to the Venditti family, and the rink hosted a regular series of special events to showcase performers.

Iceland became the home of a number of regional schools, including East Providence High, Providence Country Day and Moses Brown. When the RI Auditorium wasn’t available, Tom Eccleston often practiced his Providence College Friars at the rink. It was also a haven for figure skaters, which was especially important to the Venditti family, and the rink hosted a regular series of special events to showcase performers.

Because Iceland was an outdoor facility, it was subject to conditions indoor rinks don’t contend with – the weather. As a result, cleaning the ice and making new sheets between figure skating sessions, public skating, and hockey games was sometimes wanting. A large commercial snowblower was used to clear the ice after snowstorms. That snowblower also almost cost Anthony his ability to walk, let alone his life, when a staffer lost control of it and the blades chewed up Anthony’s leg. Doctor’s told him he might never walk again, but this was Anthony Venditti and he persevered and eventually overcame the worst of the accident.

While the injury took its toll on some of Anthony’s physical health, it did not take away his ingenuity and imagination. When the first Zamboni arrived at Lou Pieri’s RI Auditorium in 1954, it was not yet named after its inventor but simply described as “an ice re-surfacing machine”. So, of course, Anthony set out to create his own ice re-surfacing machine.

Interestingly, Frank Zamboni and his brothers had been partners in an enterprise that made and sold block ice, just like Anthony’s father-in-law. As the block ice industry declined due to mobile refrigeration, the Zamboni brothers instead used their ice making knowledge to create an indoor ice rink called, coincidentally, Iceland, in 1940.

The ice rink proved so successful that keeping the ice smooth was a constant and labor-intensive job that took a lot of time. By 1949, Zamboni created a prototype of his ice-resurfacing machine that could complete the work in fifteen minutes. Mass production of the machines began in 1954 and Lou Pieri got one of the first off the assembly line and Anthony took note.

He observed the mechanisms and imagined how they linked and worked together. He also saw how he could convert his maintenance Jeep with a hot water tank, hand controls, release valves and a large chamois to replicate to some degree the magic of the machine’s ability to efficiently lay down a new sheet of ice. And so he did – minus a scraping component. Although it was never named as such, taking a page out of the original’s legacy, we suppose it could have been called a “Venditti.” It made excellent ice.

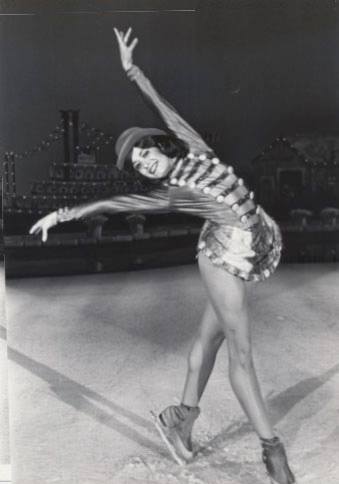

Perhaps the most famous skater to emerge from Iceland’s legacy was a figure skater, and not just any figure skater. It was Anthony’s youngest child, Anne-Marie, who learned how to skate on her father’s creation. Little Anthony, Iceland’s resident skate sharpener, was an accomplished figure skater, himself, capturing a New England Novice Championship and becoming an inspiration for Anne-Marie to do the same.

Perhaps the most famous skater to emerge from Iceland’s legacy was a figure skater, and not just any figure skater. It was Anthony’s youngest child, Anne-Marie, who learned how to skate on her father’s creation. Little Anthony, Iceland’s resident skate sharpener, was an accomplished figure skater, himself, capturing a New England Novice Championship and becoming an inspiration for Anne-Marie to do the same.

At age 11, Anne-Marie was crowned both New England’s Novice Champion and Junior Ladies Champion. That year she was also the recipient of the Dudley Richards Memorial Award, named after the USA Olympic figure skating captain who tragically died in an airplane crash with the entire USA figure skating team in 1961. His name would also grace another local ice rink in East Providence less than a decade later.

Anne-Marie would go on to skate with Holiday on Ice in Europe and later move to Hollywood, performing on the Donny & Marie television show and on Peggy Fleming and Dorothy Hamill skating specials, as well as their casino and dinner shows.

Despite every effort, the politics of the area prevented Anthony from ever installing a sign at Iceland. Word quickly got around, however, and the public’s overwhelming response to the rink convinced him that a skating rink could be a year-round proposition, so he began the process of building an indoor facility next to the outdoor surface.

With the concrete base and main steel support girders in place, Anthony had just about finished the roof when he suffered the snowblower injury. Along with his progressing pulmonary condition and ever-rising electrical costs, progress on the indoor rink stopped and never resumed, nor did the growth of the outdoor business. Iceland slowly decayed and then closed for good in the mid 60’s, its machinery dismantled and sold.

The structures stood for more than two decades, as if quietly pleading for someone to breathe new life into them. To save on taxes, the rink and its crumbling boards, along with the welcome center, equipment building, and homestead were unceremoniously razed in 1989.

The Speedway, however, remains, still well attended and proudly run by the Venditti family all these years later…with the story of Anthony’s full and adventurous life and contributions to us all preserved and memorialized in daughter Adrienne’s published saga, “The Godfather of New England Stock Car Racing”.

By RIHHOF