The New Brunswick campus of Rutgers University is widely recognized as the site of the first college football game in the USA.

The Rutgers game, played in 1869 against Princeton (then known as the College of New Jersey), was reported to have more resembled the game of soccer than the “football” we know today. Two teams of 25 players attempted to score by kicking the ball into the opposing team’s goal. Throwing or carrying the ball was not allowed, but there was plenty of physical contact between players.

Teams made up their own rules, making it difficult to find and compete with other teams. For the next two decades, the game evolved with little or no standardized set of rules and only very slowly beginning to resemble the American game we know today.

Football associations at Brown existed for several years but disappeared completely from Liber Brunensis (the Brown yearbook) from 1881 to 1886. A football association did not become firmly established at Brown until the 1890’s. By then, additional eastern college schools – Yale, Columbia, Penn, Dartmouth and Harvard, among others – had already joined the fray. Brown needed to step it up to face the competition on the horizon.

In the 1890’s, the student body at Brown was drawn largely from the local area, not from throughout the nation and beyond as it does today. It needed a “flow” of players to field and replenish a competitive team. They would have to come from the nearby secondary schools.

In 1891, under the guidance of the Brown Foot Ball Association management, an “Interscholastic Foot Ball League” for Providence secondary schools was established. The association had formal by-laws and a constitution. Significantly, as a lure, a Silver Cup was to be awarded by the Brown Foot Ball Association to the season’s best team. Standings of the teams were published in the Brunonian (the Brown newspaper) and the Bear freshman teams played some of the teams. A close relationship and a local “flow” of talent had been established.

Meanwhile, Central Falls, RI native and former Brown tennis star, Malcolm Greene Chace, and his “All-American” ice polo friends and fellow tennis stars had barnstormed Canada and brought the game of hockey back to the states. In 1898, their pioneering efforts led to Brown suiting up its first formal team and defeating Harvard 6-0 in our nation’s first intercollegiate league hockey game. Again, the question would be asked: Where would the replacements come from for the graduating hockey players?

Meanwhile, Central Falls, RI native and former Brown tennis star, Malcolm Greene Chace, and his “All-American” ice polo friends and fellow tennis stars had barnstormed Canada and brought the game of hockey back to the states. In 1898, their pioneering efforts led to Brown suiting up its first formal team and defeating Harvard 6-0 in our nation’s first intercollegiate league hockey game. Again, the question would be asked: Where would the replacements come from for the graduating hockey players?

The game of “ice polo” had already been taken up by Brown University in 1894. The Bears played against teams representing major east coast athletic clubs dedicated to the sport, such as the Brooklyn, the Cambridge, and the Passaic (NJ) Ice Polo Clubs.

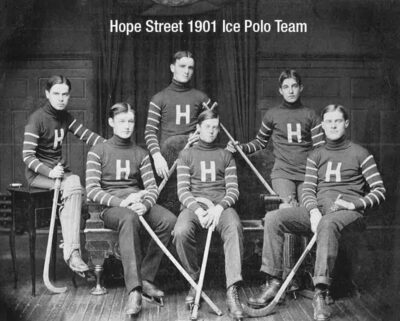

In Rhode Island high schools, ice polo was played from 1898 through the spring of 1902. Hope Street High School, as it was then called, was only a wrist shot away from the Brown campus. It had captured the title each year, sharing the crown with East Providence for two of them.

In Rhode Island high schools, ice polo was played from 1898 through the spring of 1902. Hope Street High School, as it was then called, was only a wrist shot away from the Brown campus. It had captured the title each year, sharing the crown with East Providence for two of them.

There was a great stir at Hope Street and other local high schools in the spring of 1902 when it was announced that Brown University had offered a cup, later to be named “The Brown Cup”, to be given to the best “prep school hockey team” from what was a select list of local secondary schools identified by Brown.

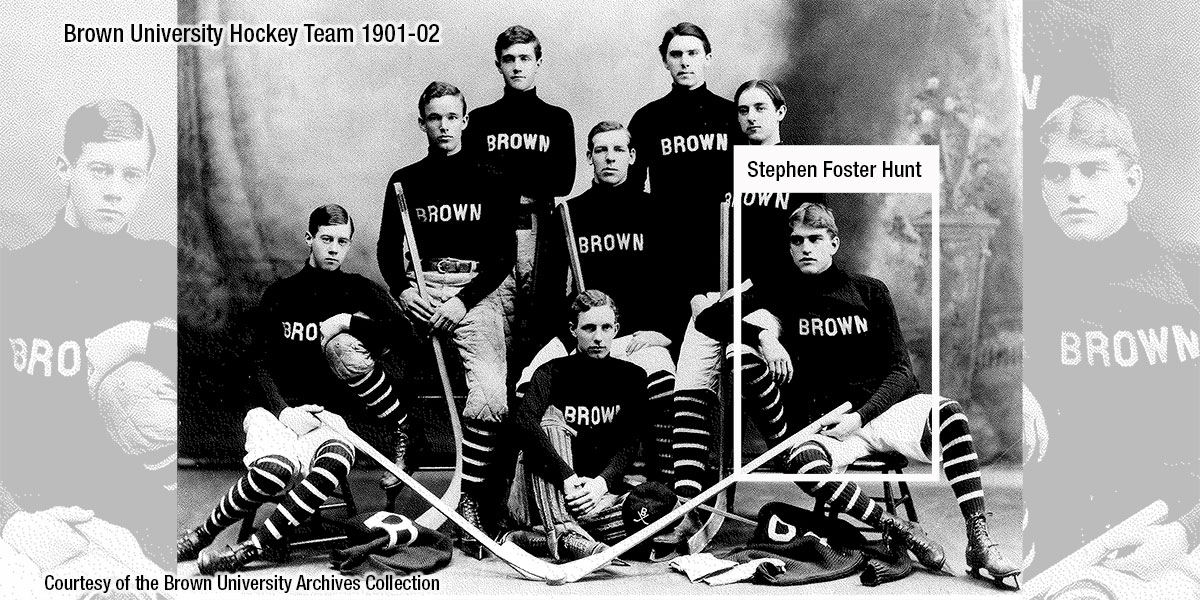

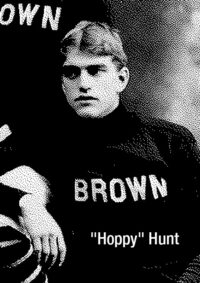

The idea was the brainchild of Brown Hockey Association manager and sophomore cover point Stephen Foster “Hoppy” Hunt who would eventually captain Brown’s 1904 team. It was an obvious duplication of Brown’s successful blueprint devised a decade earlier to recruit local footballers. According to a Providence Daily Journal article on the plan, Hunt’s objective was that “if such a league could be formed and the rudiments of the game thoroughly understood by the members of the several teams that when they entered college they would be much better prepared to try for the college hockey team.”

The idea was the brainchild of Brown Hockey Association manager and sophomore cover point Stephen Foster “Hoppy” Hunt who would eventually captain Brown’s 1904 team. It was an obvious duplication of Brown’s successful blueprint devised a decade earlier to recruit local footballers. According to a Providence Daily Journal article on the plan, Hunt’s objective was that “if such a league could be formed and the rudiments of the game thoroughly understood by the members of the several teams that when they entered college they would be much better prepared to try for the college hockey team.”

To that end, seven invited local high schools raised their hand – Hope Street, East Providence, Classical, Providence English, Manual Training, the University School, and the Lyceum Phoenix of Friends School.

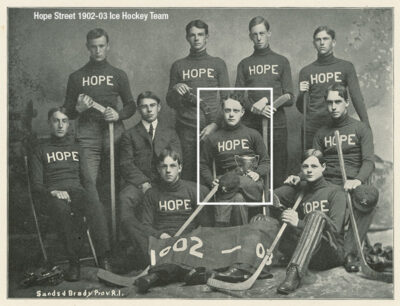

Representatives of the schools met in November of 1902 and the league known as the Brown University Interscholastic Hockey League was formed with intercollegiate rules to govern. One month later, the state’s Interscholastic League would sanction and absorb the circuit.

Like Hope Street, the University School was also located on the Providence east side close to Brown, on property now part of the RI School of Design, at the confluence of Benefit, Waterman and Angell Streets. Also nearby was the Lyceum Phoenix of Friends School. This long established Quaker educational institution, then colloquially referred to as the Friends School, is what we now know as the Moses Brown School, renamed in honor of its founder in 1913. Classical High School, Providence English High and Manual Training were located in very close proximity to each other on the city’s west side.

Since outdoor ice was not a permanent winter feature in Rhode Island, the league’s first regular season hockey schedule and that for the Brown Cup honors were necessarily short. One game with each team for both titles would have to suffice.

Without a formal coach, Hope Street was guided by its team captain and one of its ice polo veterans, Harold Grimes, and took both the Interscholastic title and the Brown Cup with a 5-0 overall record after defeating East Providence 1-0. For various reasons, including instances of no available safe ice, not all scheduled contests with all teams were played.

Of the original seven squads, Manual Training, Classical, East Providence and Hope Street would win state titles over time, with the latter dominating for nearly two decades. Providence Technical, which became Central High School in 1933, joined the league two years after its creation and won several pennants as the circuit fluctuated between four and nine teams over its first 40 years. Today, some 120 years after the league’s birth, up to 30+ hockey teams have vied each year for state crowns in several divisions.

Of the original seven squads, Manual Training, Classical, East Providence and Hope Street would win state titles over time, with the latter dominating for nearly two decades. Providence Technical, which became Central High School in 1933, joined the league two years after its creation and won several pennants as the circuit fluctuated between four and nine teams over its first 40 years. Today, some 120 years after the league’s birth, up to 30+ hockey teams have vied each year for state crowns in several divisions.

While Brown’s initiatives can easily be seen as transformative, the eagerness of their purpose did generate some controversy. With its earlier formation of a secondary school football league, Brown had made its gridiron available to its closest high school neighbors – Hope Street and the University School. Now, with the creation of the hockey circuit, it had given them, and them alone, the privilege of practicing on Brown’s outdoor rink, located on donated land behind Marvel Gym. Local editorials assailed the appearance of favoritism as unfair and “petty squabbles” ensued.

In March of 1903, at the start of the baseball season and shorty after the awarding of the first Brown Cup, individuals and other schools demanded that if Brown could not make the usage of its gridiron, rink and baseball cage available to all schools in the “Interscholastic” for equal lengths of time, it should (and eventually did) cease the practice.

By RIHHOF