Like so many other Rhode Islanders whose hockey careers are highlighted by both on- and of-ice achievement, it is impossible to categorize Henry J. Coupe, Jr. as simply either a “Player” or “Pillar” member of our nation’s hockey community for he excelled at both.

Born in 1921 in Cranston, “Hank”, as he was known, was a crafty center, scorer and playmaker. He enjoyed an exceptional schoolboy hockey career at LaSalle Academy, which he continued at the Northwood School in Lake Placid, playing for US Hockey Hall of Famer, Jim Fullerton, with whom he became a lifelong friend.

Hank, joined by All-Stater and fellow LaSalle star, Rollie Benjamin, played collegiately at the University of Illinois, which won the unofficial national championship in 1941. There, Hank studied for a career in dentistry. He led the Big 10 in scoring in the 1942-43 season that saw the Illini capture their 3rd consecutive Big 10 championship. Ironically, it would be the Fighting Illini’s last as a D1 entry due to lack of players off to serve in WWII.

That season he played for coach Vic Heyliger and alongside Amo Bessone, both of whom would later be inducted into the US Hockey Hall of Fame. Amo would go on to play defense with our RI Reds and later coach Michigan State for 28 years, leading the Spartans to the NCAA championship in 1966. The goaltender on Hank’s Illini team was Tom Karakas, brother of famed Reds and NHL great, Mike Karakas, a charter member of both the RI Reds and US Hockey Halls of Fame.

When Illinois ended their varsity hockey program, Hank transferred to Queens University in Kingston, Ontario where he became the first American-born player to skate for the Gaels in their then 60-year history. The speedy forward starred there for two years where he was dubbed “The Flash” by the local press. According to Hank’s daughter, Marilyn Caparco, “At Queens, he switched his studies to focus on engineering,” which would later become an integral part of his lifelong connection to the game of hockey. But first, there was military service.

After college, Hank enlisted in the Army, rising to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. In the Pacific theater, he would command a POW camp in the Philippines. Confident in himself but never one to feel superior to others, Marilyn recalls her father telling the family that he used his dental training to clean the teeth of some of his fellow soldiers from time to time.

After his discharge, and hockey still in his blood, Hank played in the Eastern Amateur Hockey League with the New Haven Eagles and New York Rovers. Then, in 1947, he turned professional with the Toledo Mercury’s of the International Hockey League, which had formed just 2 years prior.

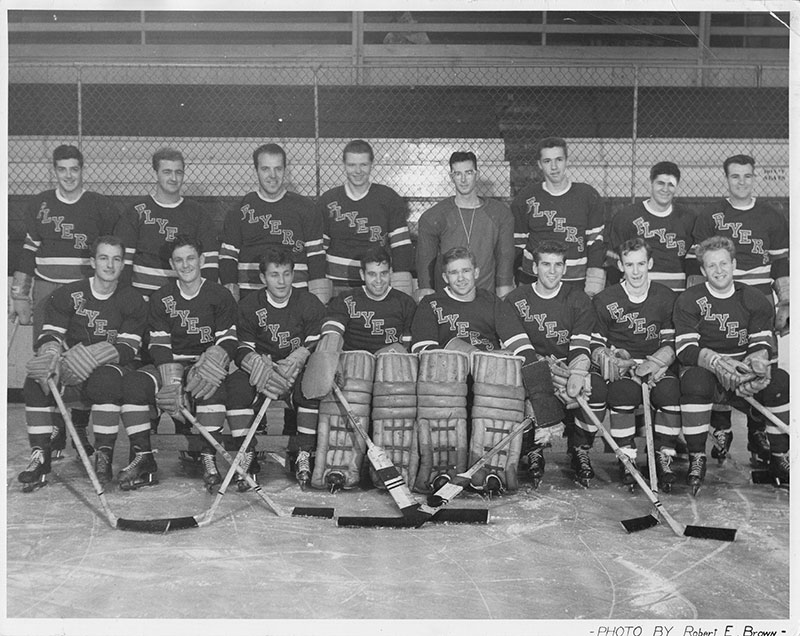

The following season, Hank signed with the IHL’s Muncie Flyers, becoming player-coach on a team that also included his younger brother, Bob, and North Providence goaltender, Al Bentley, who would later play for the Reds. That season, the Coupes combined for 19 goals and 22 assists and a berth in the league playoffs. It would be Hank’s final professional season as the Flyers, poorly financed, folded.

The following season, Hank signed with the IHL’s Muncie Flyers, becoming player-coach on a team that also included his younger brother, Bob, and North Providence goaltender, Al Bentley, who would later play for the Reds. That season, the Coupes combined for 19 goals and 22 assists and a berth in the league playoffs. It would be Hank’s final professional season as the Flyers, poorly financed, folded.

He would return to amateur play, becoming a regular in RI and New England circuits as both a player and coach for more than a decade after. During that time he coached the Brown Freshman hockey team for friend Jim Fullerton, while officiating interscholastic and college hockey games. He would become President of the RI Hockey Officials Association in 1965.

With his playing days behind him, Hank created International Ice Rink Consultants. From his RI headquarters, and working alongside his son, Bob, the firm became one of the country’s foremost rink design, engineering and installation specialists.

In the forefront of ice-making technology during that time, Bob recounts, “My father did not like Freon-based systems because of the danger of leaked gas. The energy crisis of the 70’s led him to design a new system to more efficiently freeze ice. Others adopted it and he adapted those same principles to engineer heating systems for dog tracks to facilitate winter racing.”

In the forefront of ice-making technology during that time, Bob recounts, “My father did not like Freon-based systems because of the danger of leaked gas. The energy crisis of the 70’s led him to design a new system to more efficiently freeze ice. Others adopted it and he adapted those same principles to engineer heating systems for dog tracks to facilitate winter racing.”

At its peak, his company designed and held contracts with buildings hosting professional hockey in Chicago, Anaheim, Denver, Minneapolis, Los Angeles, Oklahoma City, and Tampa, as well as college venues like Brown’s Meehan Auditorium and rinks at Holy Cross, Illinois, Norwich and Maine. Of course, there were many in RI also, including the Cranston Municipal Rink, Thayer and Mid-State Arenas, Portsmouth Abbey, and Dudley Richards. And, of course, Burrillville’s Levy Rink, the very first enclosed ice rink built for a public school in the entire United States.

“Any hockey player will tell you that good ice translates into good hockey. And good ice was what Hank Coupe was all about,” Bob is proud to say. As testimony to his reputation as the best at his profession, it was Hank who the NHL hired to engineer the ice rink to be built in the Expo Hall of the Florida State Fairgrounds for the new Tampa Bay entry into the league in 1990.

That year, Bob recalled, George Steinbrenner had become the White Knight whose infusion of money rescued Phil Esposito’s bid to establish an NHL franchise in Tampa. “The Boss” consulted with Hank to determine if a standard ice-making plant was sufficient to withstand the rigors of the Tampa heat. “It was not,” Bob remembers his dad advising. “My father recommended a system to double the ice-making efficiency and that beat the heat.”

Marilyn is proud to think of her dad as a renaissance man. “He did it all. He was an athlete, entrepreneur, and an accomplished speaker, golfer and violinist,” she boasts. Smiling, she recalls, “He would often ‘chill’ after games by playing a classical tune.”

Hank passed away peacefully in 2018 at age 96 leaving behind a legacy that covers the full spectrum of involvement in the game and leaving it so much richer for him having contributed to it.