Four years before the outbreak of World War I, Phillip Zifcak emigrated from the Slovakian region of the teetering Austro-Hungarian Empire. His wife to be, Frances, followed two years later. They met working in a textile mill in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, married, and soon welcomed the first of 13 children.

Phillip and Frances moved to neighboring Burrillville and Frances supported their children with work at a neighboring mill, for one stretch Phillip working the first shift, then taking over the childcare at 3 p.m. when he passed Frances entering the mill to work the second shift. There was not a lot of time for athletics for the kids until the Depression and World War II were in the rearview mirror and children number 11 and 12 came along, Edward and Raymond.

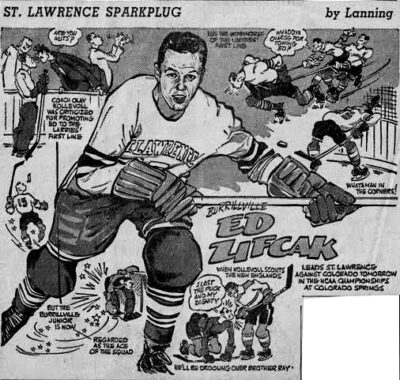

Eddie Zifcak, a smooth, swift skater with clever hands and a canon for a shot — All State, All New England, twice All American, and twice a member of the US National Team — remembers the family’s work credo very well. He remembers seeing it in practice one day when he was 13 or 14 and helping his father build a house for one of his sisters and her family.

“My father was a great carpenter. Self-taught. He could make anything. He’d come home from the mill and go out in the little shop he had out back and work for hours on all kinds of things we needed. He even built a house once for one of my sisters.”

“My father was a great carpenter. Self-taught. He could make anything. He’d come home from the mill and go out in the little shop he had out back and work for hours on all kinds of things we needed. He even built a house once for one of my sisters.”

Eddie has never forgotten the window installation.

“We were all done. At least I thought so. Got all the windows in and finished. But something about this one window bothered him. He kept measuring and measuring it, this way and that, I could see he wasn’t happy with it, but what was wrong I couldn’t tell. Finally he says, ‘Gee, it’s off by 3/16ths of an inch.'”

“‘Dad,’ I said, ‘What are you worrying about? Three sixteenths of an inch? It looks good!'”

“‘Yeah,'” he said. “‘But it’s off. And maybe nobody else will notice. But I do! I’ve got to fix it.'”

“And that was him. Everything had to be perfect. And we took that window out and took it apart and put it together again and fixed it. That was the lesson. Get it done right.”

Eddie, now 88, carried that lesson forward, and credits it for much of his success in hockey and life in general. And it was, in fact, a couple of Phillip’s earlier carpentry projects that gave Eddie his start in hockey.

First, Phillip built a little rink in the yard with 10-inch planks for boards, flooding it with a garden house. Then, instead of buying a stick for Eddie, an item destined to break anyway, Phillip simply borrowed one and copied it in his shop. Later, when Eddie was in high school, he built a regulation-size wooden goal cage so that in the off-season Eddie could perfect his shooting, snapping pucks off the slick face of a discarded refrigerator door.

With no youth hockey in that day, Eddie learned the game through a progression of pond hockey competitions. The neighborhood “Briar Hole” came after the backyard rink. It was a small shallow pond surrounded by bull-briars that made errant puck retrieval delicate and sometimes painful. The briars, Eddie feels, were instructive about the need for accurate passing and shooting. The neighborhood dads would come out to shovel it off when it snowed.

“Hockey was very popular in town, and the parents did whatever they could to help us. They were all very supportive. Even my mother. She was actually more interested in sports than my father. She was a big Red Sox fan. She became a big hockey fan, of course, when I got to high school.”

The next step was Ross Pond, nearly a mile’s walk from home. The best kids and many of the best adults in Burrillville would play games from morning to sundown on weekends.

“That’s where I learned to stickhandle and carry a puck. A lot of those guys were good, and you didn’t have six guys on a side, more like ten, so you either learned to carry a puck or you didn’t play.”

“That’s where I learned to stickhandle and carry a puck. A lot of those guys were good, and you didn’t have six guys on a side, more like ten, so you either learned to carry a puck or you didn’t play.”

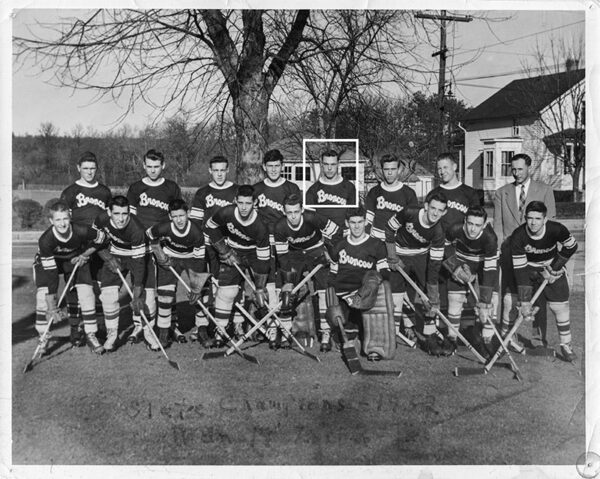

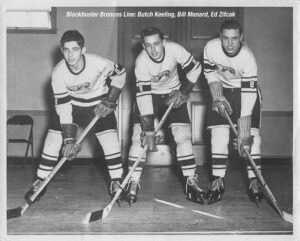

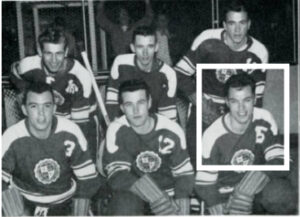

Eddie took his first shifts at wing on Tom Eccleston Jr’s Burrillville High School 1949 state champions. He became a major contributor during his sophomore season when he teamed with Billy Menard and George Keeling to form one of the most memorable lines in BHS history, helping to lead the Broncos that year to their first appearance in the New England Tournament championship game. His junior season, Eddie had the odd distinction of making second team All-State but first team All-New England as he co-starred with Larry Gingell to lead the state champion Broncos to within a goal of the New England title in one of the most dramatic games in tournament history, a 3-2 triple overtime loss to St. Dominic’s of Lewiston, Maine.

In his senior season, Eddie was a unanimous All-State first team selection as the Broncos again won the state championship, though a shocking overtime loss in the first round of the New England’s precluded further honors.

In his senior season, Eddie was a unanimous All-State first team selection as the Broncos again won the state championship, though a shocking overtime loss in the first round of the New England’s precluded further honors.

Meanwhile, Eddie had excelled in football as an All-Class running and defensive back on two championship teams and was especially adept at baseball. When the Broncos defeated LaSalle in the 1950 state championship series, sophomore Eddie was the winning pitcher of game one; then, in game two, at center field, he caught the final out. And when the Broncos returned to the state title series his senior season, narrowly losing to Woonsocket, Eddie was chosen All-State first team at second base.

Though a National Athletic Honor Society student as well, Eddie was shocked when none of the colleges that had accepted him offered the full scholarship that he and his family had to have. There seemed nothing to do but stay home and work for a year when a chance encounter with a former Bronco teammate changed his fortunes. He bumped into Jackie Boylan, just home from his freshman year at St. Lawrence University.

Boylan, the Bronco goaltender during Eddie’s sophomore and junior seasons, had won a state championship and twice led the Broncos to the New England Finals. Though merely chosen second team All-state as a senior, as a freshman at St Lawrence, Boylan beat out two upper classmen for the SLU starting job and then he led St. Lawrence to its first appearance in the NCAA “Final Four” tournament in Colorado. Incredulous that no college with hockey ambitions would offer his friend a full ride, he urged Eddie to “Write to Oley!”

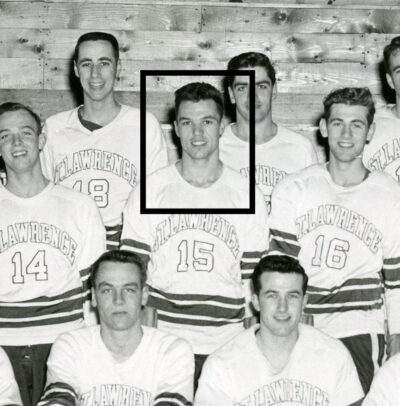

“Oley” was coach Olav Kollevoll, the young Norwegian-born Canadian who transformed miniscule St. Lawrence into the national hockey power it remains today, twice leading the Larrys (as they were then colloquially nicknamed, but now officially the “Saints”) to the Final Four tournament in just five seasons behind the bench. Eddie duly wrote and followed up with an application, impressing both Kollevoll and the admissions office enough to award him a full scholarship.

St Lawrence competed in the Tri-State League, a small conference that included Clarkson and RPI and made a big national impact. It was then a small school conference as well, and its rules allowed freshmen to play varsity in an era when most conferences did not.

Eddie was not intimidated. He debuted on the second line, centered by All-American upper classman Brian McFarlane, famous later as the host for 28 years of Hockey Night in Canada. The McFarlane line scored 42 goals that season, with Eddie potting 11 and assisting on 14.

Another teammate was Bill Torrey. While not a regular for the Larrys, hockey remained his passion and he delved into hockey management after college. Working his way up to general manager of the New York Islanders, he would go on to engineer teams that won four consecutive Stanley Cups in the early 1980s, later becoming the architect of the Florida Panthers.

Another teammate was Bill Torrey. While not a regular for the Larrys, hockey remained his passion and he delved into hockey management after college. Working his way up to general manager of the New York Islanders, he would go on to engineer teams that won four consecutive Stanley Cups in the early 1980s, later becoming the architect of the Florida Panthers.

Eddie notched similar modest figures the following season before breaking out his junior year on the first line with a 20-26-46 output, a point shy of McFarlane’s team-leading mark. SLU’s record earned the Larrys their second trip to the Final Four. SLU lost a 2-1 squeaker to Colorado College in the semi-final — with Eddie scoring the goal — and then lost the consolation to Harvard. But Eddie’s personal consolation was a berth on the UPI’s All-American Team. Back at St. Lawrence, he took up his baseball glove and batted .400 that season while patrolling center field.

Eddie was elected co-captain his senior year, and the hockey campaign began as a Burrillville reunion of sorts. Kollevoll had moved on, and George Menard, BHS class of ’45, took over the hockey and baseball reins. Menard had been an All-East defenseman at Brown and played three years of minor league baseball for the Yankees. The product of a large family of modest means much like Eddie’s, he knew the value of hard work and could convey the message, quietly but unmistakably, to his players. “Soft spoken, but strict,” Eddie described Menard. “Not a yeller. He knew what he was doing. Everybody liked him, just like they liked Oley. The transition to George was very smooth.”

Eddie was elected co-captain his senior year, and the hockey campaign began as a Burrillville reunion of sorts. Kollevoll had moved on, and George Menard, BHS class of ’45, took over the hockey and baseball reins. Menard had been an All-East defenseman at Brown and played three years of minor league baseball for the Yankees. The product of a large family of modest means much like Eddie’s, he knew the value of hard work and could convey the message, quietly but unmistakably, to his players. “Soft spoken, but strict,” Eddie described Menard. “Not a yeller. He knew what he was doing. Everybody liked him, just like they liked Oley. The transition to George was very smooth.”

Indeed, hardly skipping a beat, St. Lawrence went 18-4 that season and once again returned to Colorado Springs for the Final Four tournament where the Larrys played well, losing an overtime heartbreaker to champion Michigan in the semi-final; then trouncing Boston College for third place.

Sadly, however, Eddie and three senior teammates were disallowed from play by an NCAA rule that limited participants to just three seasons of varsity play. SLU’s Tri-State League was an outlier, of course, allowing varsity eligibility for freshman and hence four seasons of play. Clarkson’s situation was worse. They had been undefeated in the east at 20-0, but facing a crippling loss of seven players to the NCAA rule, they declined their invitation. Yet the season remained a great success for Eddie Zifcak as he was again named an All-American, this time by the American College Hockey Coaches Association (ACHCA).

Sadly, however, Eddie and three senior teammates were disallowed from play by an NCAA rule that limited participants to just three seasons of varsity play. SLU’s Tri-State League was an outlier, of course, allowing varsity eligibility for freshman and hence four seasons of play. Clarkson’s situation was worse. They had been undefeated in the east at 20-0, but facing a crippling loss of seven players to the NCAA rule, they declined their invitation. Yet the season remained a great success for Eddie Zifcak as he was again named an All-American, this time by the American College Hockey Coaches Association (ACHCA).

Shortly before graduation, Eddie received the first of two eventful invitations. It was U.S. Amateur Hockey Association inviting him to try out for the United States National Team, scheduled to tour the U.S. and Europe the next season and compete in the World Championship tournament in Moscow. Sixty players would begin try-outs on Oct. 1 at the Boston Arena.

Returning home for the summer, Eddie was delighted to learn that his old Bronco teammates, George Keeling and Eddie Yagnesek, had also been invited. When the tryouts began, the three friends commuted together to Boston.

Returning home for the summer, Eddie was delighted to learn that his old Bronco teammates, George Keeling and Eddie Yagnesek, had also been invited. When the tryouts began, the three friends commuted together to Boston.

However, shortly before the try-outs, Eddie got the second consequential invitation. It was from Uncle Sam, inviting him, with no option for refusal, to join the United States Army team — infantry, not hockey. He was to report to Fort Dix for basic training in the middle of the hockey try-outs.

“I didn’t know what to do,” said Eddie. “So, I called Jack Mately, the team business manager. ‘Don’t worry,’ he said. ‘I’ll get you out.’

“Mately had to talk to some colonel at the Pentagon who oversaw athletics for the entire Service. But a couple of weeks went by, and I didn’t hear back from him. Finally, the day before I had to report to Fort Dix, I called him again. ‘I’m still working on it,’ he said. ‘Don’t worry at all. You just get on the bus and report. I’ll get you back out here in a few days.'”

It was more like two weeks. But at least Eddie didn’t have to start basic with the other draftees. He was put up in a special barracks and didn’t even have to get his head shaved.

“Finally, I got an order to report to Fort Banks just outside of Boston. It was called Temporary Duty. I could stay at Fort Banks as long I was on the team. I didn’t have to wear a uniform, either. I was there with maybe four or five other guys from the hockey team who were also in the service. An Army vehicle would drive us through the tunnel to Boston every morning, take us back to the fort for lunch, then back to the rink for the afternoon session and then pick us up again. But the first thing they had to do for me when I got to the fort was drive me back home to Burrillville to get my hockey bag! You should’ve seen the looks we got when we pulled up at the house!”

After some local exhibition games and a final move from the Boston Arena to the Bowdoin College rink in Maine in November, final cuts were made and after Christmas the team embarked on an grueling 18-game January tour of the Midwest in preparation for a brief European schedule prior to the World Championship tourney in Moscow.

The coach was Bill Stewart, former NHL referee, National League umpire, and the first US-born coach to win a Stanley Cup, with the Blackhawks in 1938.

Eddie’s roommate was Bill Cleary Jr., the future scoring star of the 1960 Olympic US Gold Medal winning team and, later, Harvard’s most successful head coach. Four other future 1960 Olympians were on the squad, too, including the captain, Jack Kirrane, and the legendary University of Minnesota star, John Mayasich.

The Midwestern tour had hardly begun, however, when the team got the bad news. The State Department ordered the U.S. team to boycott the World Championship in protest of the Soviet Union’s suppression of the Hungarian revolution the previous October. It was a disappointment, but the team understood the reason and accepted it.

Nevertheless, the European tour proceeded in February. Playing in outdoor stadiums before enthusiastic crowds of thousands, they toured Scotland, England, France, Switzerland, Italy, Germany, Sweden, and Norway. They were greeted cordially everywhere, though sometimes booed by local crowds who were not familiar with the physical style of North American play.

The team turned in a sterling 23-3-1 record, including a win over the Swedish national team, which had edged the Russians to win the World Championship in Moscow. Eddie could only speculate about what the team might have achieved had history taken a different turn. “We had a very strong team and I think we would have done pretty well if we had been in the tournament.”

The team turned in a sterling 23-3-1 record, including a win over the Swedish national team, which had edged the Russians to win the World Championship in Moscow. Eddie could only speculate about what the team might have achieved had history taken a different turn. “We had a very strong team and I think we would have done pretty well if we had been in the tournament.”

Once back in Boston, Eddie’s idyll at Fort Banks along with his Temporary Duty status continued for a surprising time before the Army bureaucracy remembered him, and it was off to Fort Dix for Basic Training at last. But at mail call one day, he got the happy news that AHA was inviting again to try out for the 1957-58 National Team, and the Army cut him an order to report to a Naval Air Station outside of Minneapolis in November where the tryouts would be held at the University of Minnesota rink.

All the servicemen candidates would be tried out first, the civilians would be added to the mix in December, and final cuts would be made just before Christmas. The three-week 1958 World Championship tournament would be played in Oslo, Norway, beginning Feb. 28. To prepare, the team would play a 25-game schedule beginning in the U.S. before Christmas and extending to Europe before the tournament began.

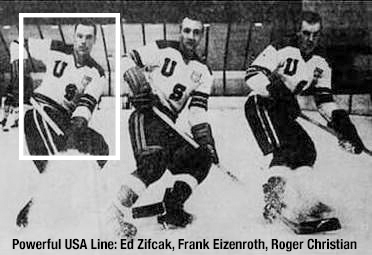

The coach was Minnesotan Cal Marvin, who had made his reputation behind the bench in the top ranks of the Great Lakes region men’s amateur circuit. Eight of the players would be on the 1960 Olympic Gold Medal winning team, including Bill and Roger Christian, the heroes of the 3-2 victory over Russia at Squaw Valley.

But the preparatory schedule may have been too grueling. Injuries piled up and the team virtually limped into Oslo for the World tournament, with the toll growing worse as the games proceeded. They shellacked a weak Polish team, 12-4, in the opener. But Sweden, a team they had beaten in ’57, dealt the undermanned U.S. team an 8-3 dose of reality. The Americans recovered with a 6-1 win over Norway before a raucous crowd of 3,000 jeering and booing homers who resented the Yanks’ physical style of play, at one point hurling a liquor bottle that narrowly missed goalie Willard Ikola’s head.

But the preparatory schedule may have been too grueling. Injuries piled up and the team virtually limped into Oslo for the World tournament, with the toll growing worse as the games proceeded. They shellacked a weak Polish team, 12-4, in the opener. But Sweden, a team they had beaten in ’57, dealt the undermanned U.S. team an 8-3 dose of reality. The Americans recovered with a 6-1 win over Norway before a raucous crowd of 3,000 jeering and booing homers who resented the Yanks’ physical style of play, at one point hurling a liquor bottle that narrowly missed goalie Willard Ikola’s head.

USA’s best game came next, a 2-2 tie against highly regarded Czechoslovakia, which had tied Russia 4-4. But now, having lost two forwards, plus Mayasich, the soul of the club, the Americans did well in the next game to hold Russia to four goals against one of their own. But the Russian game cost the U.S. yet another player, and fielding a team of just 12 men, the roof fell in against Canada’s “Whitby Dunlaps,” who pasted the Americans 12-1. Besides the sting of that score, Eddie remembers the competent play of one of the Whitby’s defensemen, Harry Sinden.

Rallying at last to defeat Finland, 4-2, in their final contest, the battered Americans finished 5th behind the Czechs while the Canadians beat Russia for the Championship. But the American’s European tour was not yet over. After a pair of post tournament wins over teams in Switzerland, the Americans headed for Moscow for two more cracks at the Russians.

“It was the Cold War, you know. You didn’t know anybody who visited Russia,” recalls Eddie, “Everybody, of course, was a little bit nervous. Like how we would be treated and that. But they were very nice to us. Very friendly. They had something for us to do every day. They even gave us pocket money. They took us on tours around the city. We stopped places and walked around — Lenin’s Tomb and the Kremlin and other places. People we met were very nice. Curious, you know, to meet Americans. And the Russian players, they didn’t speak much English, but off the ice they were friendly to us just as hockey players are anywhere.”

One thing Eddie remembers vividly. The Russians’ conditioning.

“When we were at the tournament in Oslo, we were in the same hotel as the Russian team. And, you know what, they never took the elevator. They would run up the stairs! Every time! I don’t know if it was coach’s orders, or if they were trying to intimidate us. But that’s what they did. They just ran up the stairs! All the time!”

Both nights the arena was SRO with 14,000 fans who actually cheered the American goalies when they made good stops, both of whom had outstanding games. Though badly outshot the first night, the crippled Americans lost to the Russian National “B” team only 2-1. More surprising was the next night facing the Russian “A” team, the runners- up for the World title. The Americans trailed by a goal into the final minute until the Russians put it away on a breakaway.

Games in Czechoslovakia, Germany, England, and Scotland followed before the tour ended. Their total European record was 11-16-2.

Games in Czechoslovakia, Germany, England, and Scotland followed before the tour ended. Their total European record was 11-16-2.

“The experience was just great. The hockey a little disappointing. We were hurt, of course, and I think our ’57 team was also stronger. It was too bad we couldn’t have played in the tournament that year in Moscow. I understand why we didn’t go. But if we had played, I think we would’ve done better. We did beat the champs, Sweden.”

Back at the Naval Air Station in Minnesota, Eddie and his servicemen teammates lounged around for a couple of weeks before orders came for everyone to report back to their units. Eddie returned to Fort Dix, where he completed his term of service that autumn.

Eddie figures that of the 24 months he was in the Army, he spent nearly twelve of them wearing a hockey uniform.

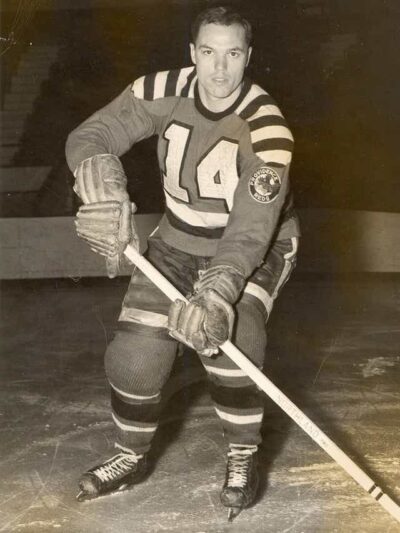

Eddie’s hockey career on the biggest stage was over. While he did play briefly for an experimental Rhode Island Reds farm team, Eddie would play most of the next decade in the top ranks of the New England senior amateur hockey circuit. For most players of his caliber, that was the only reasonable avenue of play, with the pro hockey route restricted by an NHL comprising just six teams. Consequently, top regional amateur rosters were a “Who’s who” of New England college All-American, National Team, and Olympic veterans. A fair number were former U.S. team comrades of Eddie’s.

Among the teams that recruited him were the Providence Scarlets, and after he married and settled in Templeton, Massachusetts, the Estes clubs of Rockland and Hingham. His 1962 Estes Club of Rockland won the National Amateur Hockey Association championship. When the club moved to Hingham in ’63, they were the National runners-up. Later in New Hampshire, his Nashua Royals dominated the Granite State League before he starred with the Lawrence, Massachusetts, Royals later in the decade.

Among the teams that recruited him were the Providence Scarlets, and after he married and settled in Templeton, Massachusetts, the Estes clubs of Rockland and Hingham. His 1962 Estes Club of Rockland won the National Amateur Hockey Association championship. When the club moved to Hingham in ’63, they were the National runners-up. Later in New Hampshire, his Nashua Royals dominated the Granite State League before he starred with the Lawrence, Massachusetts, Royals later in the decade.

Eddie coached youth hockey in the Gardner, Mass., area, and during the summer, the former pitcher, All-State second baseman and collegiate outfielder lit up the Massachusetts senior amateur softball circuit with his arm and his bat for a Gardner area team.

Reflecting on his athletic career and life in general, Eddie lays great credit on his upbringing in Burrillville, his family, the town’s nurturing community, and particularly the teachers and coaches he had at Burrillville High School who prepared him for the larger world.

“I think we were very fortunate. For a small town, a small school, to have everything we had. I mean, you probably didn’t realize all of it at the time, but as the years go by you say, ‘It’s unbelievable.” That’s the way I think of it.”

by Bill Eccleston