The new facility was hailed as being “of vital importance to the growth of Providence and of infinite value to the State of Rhode Island at large.” Indeed, its capacity would be greater than that of the Boston Arena (later re-named Matthews Arena), which had a max seating capacity of slightly over 5,000.

Thankfully for Rhode Island hockey, the building was the dream of Providence resident and textile executive, Hubert C. Milot, an avid hockey enthusiast who recognized our state’s passion for the game and was committed to invest in and manage it. At the time, most other buildings of this type were simply assembly halls, built as economic engines for their respective communities and not equipped with a feature like an ice rink.

Indeed, the idea for professional hockey and a venue to showcase it in Providence was likely sown nearly two decades before they were eventually realized.

Milot, who operated a textile mill in Olneyville with his brother, was born in New Bedford in 1888. His family moved to Providence at an early age and Hubert was educated at LaSalle Academy. He attended St. Mary’s College in Montreal, where he was immersed in the Canadian obsession with ice hockey. Among his classmates was Leo Dandurand, a hockey-playing American, who would later own and operate the Montreal Canadiens. He would later play a significant role in fostering Providence’s professional hockey fortunes.

As Milot observed the escalating popularity of hockey here in Rhode Island, the National Hockey League’s was loudly expressing a desire to expand beyond Canadian borders. Hubert became convinced of the potential for Providence to acquire an NHL franchise despite having no hockey rink at the time.

In 1924, representatives of several American cities responded to NHL overtures to make their case to join the league. New York was the first and then, in the early spring of that year, the 34-year-old Milot was next. He traveled to Montreal to sound out the possibilities of Providence acquiring a franchise. The following quote was attributed to him: “There are tremendous proclivities there. Providence is the centre of a thickly populated district of fine sporting proclivities and hockey is now extremely popular. Thousands are out skating at every opportunity.”

Upon his return to Providence, Hubert set his sights on creating a showcase for sports that would surpass any other venue in New England. Meanwhile, Boston and other major cities had also put their hats in the ring.

Milot’s dream was championed by U.S. Senator Jesse H. Metcalf, who headed the committee charged with forming the corporation that would control and promote the facility. It would be known as “Rhode Island Auditorium, Inc.” An aggregate mortgage of $300,000 was in place with the balance for construction to be raised by investor stock issue.

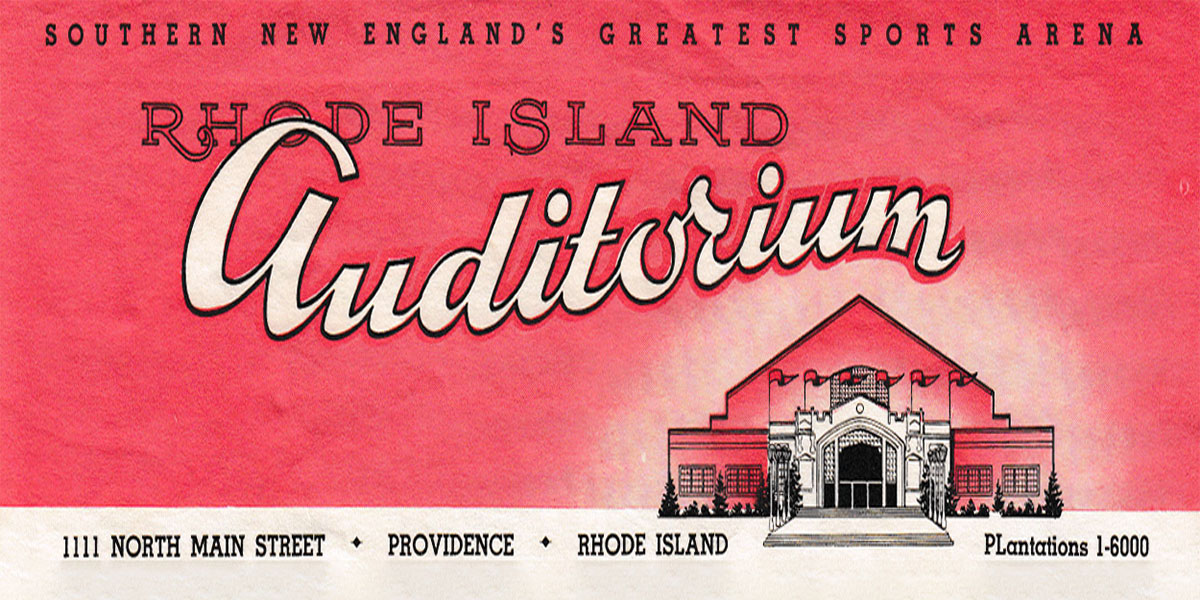

Its location at the now fabled 1111 North Main Street address, was selected for its “accessibility from the most popular centers of the State…at the very heart of the most populous area of the State and available for interscholastic athletic meets, conventions, balls, carnivals, ice hockey and the like.” The development of the area, which included the nearby 13,000-seat Providence Cycledrome, home of the NFL’s Providence Steam Roller, was spurred by North Main Street having recently been designated as Route 1 by the U.S. Highway System and that it would be serviced by public streetcars.

While the first news reports announced a June construction start, the general contract for the new Auditorium wasn’t awarded until August 22, 1925. It went to the building firm of A.W. Merchant, Inc. The man who headed the company, Archie Merchant, would later be instrumental in assuring the future of the building during the Great Depression while in a different but influential capacity.

Construction began in earnest the very next day with the public pronouncement that it would be ready in a mere six months. That would seem a pipe dream even in this modern day but the forecast was not only met but came in ahead of schedule. The Auditorium opened on February 27th, 1926, although it did not reach the finish line without incident or without changes.

In December, an ironworker fell to his death and three others were seriously injured when a steel truss being hoisted into the air broke away and they plunged 70 feet to the still-wet concrete floor below.

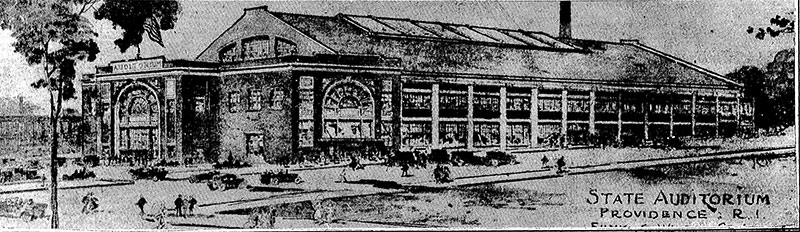

Seating, which was originally set at 8,000 (some news accounts proclaiming 8,600), had been reduced to 5,600, still more than Boston Arena but 30% less than planned. (note: there are reams of articles with announced Auditorium attendance well beyond seating capacity but that was before legal limits were set and enforced for safety). And much of the ornate exterior and interior detail on the original architectural renderings, such as chandeliers in the lobby, was absent. Reasons would be traced to underestimated or rising construction costs or perhaps also related to a less than robust sale of stock for the balance of the construction tab.

Although brand new, the building could not truly be considered state-of-the-art. Indeed, its ice-making machinery was bought from a brewery and was already 15 years old when it was installed. The patented ice-making system it drove, however, was the very same that the Boston engineering firm, Monks & Johnson, would later install at Madison Square Garden in NYC.

The grand opening was especially grand. Hailed as “The Entertainment Palace of Southern New England”, floodlights shone on the word “ARENA”, which adorned the large gable end on the front façade of the building. Patrons entered the lobby through five sets of double doors framed by an archway that encompassed a marquee that would eventually be emblazoned with a neon-lit “R.I. Auditorium” sign above a changeable backlit placard to post coming attractions.

The grand opening was especially grand. Hailed as “The Entertainment Palace of Southern New England”, floodlights shone on the word “ARENA”, which adorned the large gable end on the front façade of the building. Patrons entered the lobby through five sets of double doors framed by an archway that encompassed a marquee that would eventually be emblazoned with a neon-lit “R.I. Auditorium” sign above a changeable backlit placard to post coming attractions.

The festive inaugural evening was broadcast on WJAR radio. After formal dedication ceremonies and a swell of patriotic pomp and pageantry to acknowledge local dignitaries, the show began, featuring 14 events, including several world-class figure skating exhibitions, speed skating, barrel jumping, and a “burlesque hockey match”.

The latter gave the crowd a preview of the dangers of the game when a collision knocked out one of the players as a blade opened a gash over his eye. He was carried off the ice in his blood-drenched sweater but returned to play to the cheers of the fans – a scenario displaying the resilient characteristic of hockey players that would be repeated and admired many times over the life of the arena.

After the festivities, patrons who had paid $.85 for general admission or up to four times as much for a box seat were invited onto the ice for public skating. The following day was less than festive when authorities surprisingly scuttled scheduled public skating with the enforcement of Rhode Island’s archaic Blue Laws, which prohibited such “entertainment” on Sundays. Those statutes would immediately be challenged and eventually overhauled. Public skating would soon thereafter be enjoyed by throngs who flocked to the arena to sample and glide on the artificial ice.

The first college and schoolboy hockey games ever played indoors in RI were contested at the new Auditorium on the following Wednesday, March 3rd, when Boston College and Pere Marquette, a leading senior amateur team from Boston and the Eastern League, played to a 5-5 tie. When that game ended, Technical High School and a LaSalle Academy club team took to the ice for a non-league exhibition with Technical defeating the Rams 8-1.

Prior to the Technical-LaSalle match, high school play had been dormant for more than a month due to heavy snowfalls. The Auditorium generously offered its ice for the RI Interscholastic League to finish its season indoors and they jumped at the opportunity. Meaningful league play finally resumed at 9 am the following Saturday morning, March 6th, and the three Saturday mornings thereafter, foiling Mother Nature’s attempts to bring a premature end to the hockey season. Hope Street met Cranston in that first Saturday contest. At season’s end, the East Providence Townies prevailed, winning the first RI Interscholastic League championship played indoors and at the Auditorium.

Brown University’s hockey program, one of the first in the nation, had been dormant for 20 years when students organized class teams to play each other in the new arena that winter. The popularity and skills exhibited in those games and the new availability of indoor ice prompted the University to officially reinstate the varsity hockey program in the fall of 1926. They hired James H. Gardner, the coach of the Reds, to take the helm of the new Brown team. Brown would vacate 1111North Main when Meehan Auditorium opened on campus in 1961.

Brown University’s hockey program, one of the first in the nation, had been dormant for 20 years when students organized class teams to play each other in the new arena that winter. The popularity and skills exhibited in those games and the new availability of indoor ice prompted the University to officially reinstate the varsity hockey program in the fall of 1926. They hired James H. Gardner, the coach of the Reds, to take the helm of the new Brown team. Brown would vacate 1111North Main when Meehan Auditorium opened on campus in 1961.

Providence College also saw a future in ice hockey with the opening of the arena, suiting up its first official team in 1926. Unfortunately, it immediately fell victim to the great demand for ice time. Unable to procure enough for practice and games for the following season, the team was disbanded. The Friars would not organize an official team again for 26 years when the Auditorium again became their official home.

The building’s demise coincided with the construction of PC’s Schneider Arena, which opened in 1973. For a time, the Friars would play their home games at Meehan, while the college petitioned the city to use the seats from the Auditorium for their new arena. The city rejected the request because the construction and small dimensions of the seats no longer met local codes.

The first face-off ever between the colleges also took place at the Auditorium. The resurrected Bears and the debuting Friar sixes battled for the first time on March 1, 1927. Brown prevailed 4-1. “The game was without question the best of the intercollegiate variety played on the local rink this season,” reported the Providence Journal, “and the enthusiastic crowd, although small, was kept at a high pitch throughout the 60 minutes.”

From the outset, Auditorium management was successful in forming several adult amateur circuits, the first of which was a league recruited and made up of six large industrial concerns located in and around the Providence and Pawtucket area. All-Star teams were also assembled to compete regionally and nationally, first among them was the RI Scarlets, headed by Hubert Milot, himself.

Meanwhile, the National Hockey League had quickly expanded, adding their first American city and team, the Boston Bruins, which took up residence in the Boston Arena in 1924. Rumors had surfaced that yet another professional league was about to form and that the RI Auditorium was being considered to host a new team in it. Rumor became fact in 1926.

The Canadian-American Hockey League (Can-Am League) was established in the fall of that year with the considerable effort and influence of Milot, the Boston Arena’s George V. Brown and Judge James E. Dooley, a prominent attorney with strong political ties and a love of sports. He would also serve as President of the league for six years.

The announcement that the Auditorium would be home to a Providence entry in the new league was met with great local excitement and expectation. Dooley’s “Providence Reds” would join the Quebec Beavers, Boston Tigers, New Haven Eagles, and Springfield Indians to round out the new circuit.

The announcement that the Auditorium would be home to a Providence entry in the new league was met with great local excitement and expectation. Dooley’s “Providence Reds” would join the Quebec Beavers, Boston Tigers, New Haven Eagles, and Springfield Indians to round out the new circuit.

Interestingly, a complex relationship was also created. Some would say “conflict” in that Hubert Milot, co-owner/General Manager of the Auditorium and Dooley’s landlord, was also an owner in control of the competing Quebec franchise while Dooley reigned as the league President.

On Friday, December 3, 1926, months after hockey had already established itself as the most popular attraction there, the Providence Reds (known locally from that day forward as the Rhode Island Reds) skated onto Auditorium ice to face off against the Springfield Indians and officially becoming the building’s main tenant. Professional hockey was born in Providence and one of pro hockey’s oldest rivalries was about to begin.

On paper, it was the Reds, a club assembled with talent provided by the Montreal Canadiens that was projected to be the class of the new Canadian-American Hockey League. But not that night and not that season.

Approximately 2500 fans, among them a large contingent of dignitaries, attended the game, hoping for a storybook ending. It was not to be. The Indians took it to them, winning handily 7-1. Late in the third period, a shutout was averted with the Reds’ historic first goal, scored by center Joseph Hector “Hec” Lepine, a year earlier a linemate of the legendary Howie Morenz back in Montreal.

The Reds finished their inaugural season fourth in the 5-team league. But the fire had been lit. By the first game’s end, coach Jimmy Gardner’s charges began to flash the talent and chemistry fans would soon come to know as they would skate to 3 Fontaine Cups and league titles over the next 7 Can-Am campaigns.

In 1928, Milot sold his interest in the Quebec Beavers and months later, in 1929, Louis A.R. Pieri, a Brown grad and part-time Auditorium employee familiar to the building’s directors as a bright promoter, was named the new General Manager of the Auditorium. That appointment would set the successful course of the arena’s future. But first there were some incredible obstacles for the Auditorium to overcome – the Great Depression, a foreclosure, and an auction.

The short funds that resulted in a compromise of seating capacity and architectural detail imagined but not realized at the Auditorium’s conception struck again. The stock market crashed in October of 1929 and by 1932 the Great Depression had taken its toll. Revenues were suffering. Jobs were scarce, attendance was down, and events were difficult to secure.

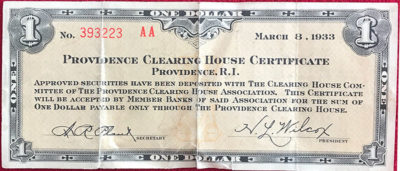

Dooley’s Reds were doing their part, winning and drawing decent crowds. But all was not rosy. The players were being paid, for a time at least, with scrip, a substitute paper currency used in the local economy here and in parts throughout the nation because regular currency was unavailable. But, at least they were being paid.

Dooley’s Reds were doing their part, winning and drawing decent crowds. But all was not rosy. The players were being paid, for a time at least, with scrip, a substitute paper currency used in the local economy here and in parts throughout the nation because regular currency was unavailable. But, at least they were being paid.

The R.I. Auditorium, Inc., on the other hand, could not make its mortgage payments and Hospital Trust National Bank, the mortgage holder, foreclosed. Lou Pieri was named receiver by the courts, unusual in that he was not a neutral third party as is traditionally the case. He would continue to operate all aspects of the property until it was put up for auction.

The big question: if the Auditorium did not find a buyer or the right suitor what was to become of hockey?

Legal notices of the public auction were first advertised on October 3rd, 1932. The auction was held on November 1ston the front steps of the Auditorium with 14 people in attendance – most of them noteholders, among them, Malcolm Greene Chace, the Central Falls native and textile industrialist considered the “Father” of ice hockey in the United States, and Archie Merchant, now president of the Providence Chamber of Commerce.

Their nominee was Arnold Jones, a sharp and well-connected RI businessman perhaps more well known to some as one of the nation’s top tennis players. He was the only bidder, handing over a check for $4,100, ten percent of his purchasing bid of $41,000 for the Auditorium, which had an assessed valuation at the time of $277,000.

Fortunately for hockey, he and those he represented were the right suitors. The Auditorium and hockey had been rescued and great celebrations and more great history would follow.

In October of 1939, the Auditorium purchased the Reds from Dooley and team GM, Jean Dubuc, with a financial assist from concessions magnate Louis Jacobs (think Boston Bruins) for a sixty-year contract to sell peanuts, popcorn, soda and Cracker-Jack. Soon thereafter, the Pieri family took over ownership of the building and the team. More championships followed and Pieri’s skills enabled the Auditorium to flourish while he rose to prominence as one of the most astute and successful sports and entertainment promoters of the 20th Century.

After Pieri’s death following a heart attack in June 1967, his son, Louis, took over the management. Not long thereafter the Reds and the Auditorium were sold to local businessman George Sage. Attendance stayed solid, but the arrival of the new downtown Providence Civic Center in 1972, with its modern amenities and a seating capacity of 11,000+, rendered the “old barn” obsolete while ushering in a new era..

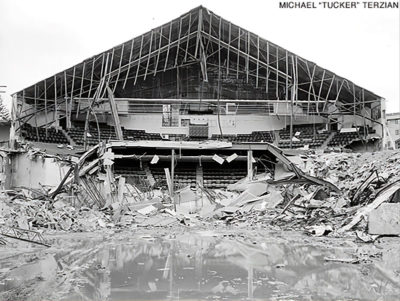

The Reds’ final game was played there on April 12, 1972. The building was now 46 years old and tired. The game had moved on and fans were still viewing the action through chicken wire. The Reds history at the Auditorium ended like it began – with a loss – this time 5-4 in overtime to the Boston Braves before 4,507 still-adoring fans. Unfair, if you think about it, because it had brought so many such great joy for so long.

The Reds’ final game was played there on April 12, 1972. The building was now 46 years old and tired. The game had moved on and fans were still viewing the action through chicken wire. The Reds history at the Auditorium ended like it began – with a loss – this time 5-4 in overtime to the Boston Braves before 4,507 still-adoring fans. Unfair, if you think about it, because it had brought so many such great joy for so long.

After Sage moved the Reds downtown, various attempts were made to keep the building alive. None lasted. In 1989, the Auditorium was unceremoniously torn down. Bricks were rummaged and seats spirited away as reminders of a golden age to several generations.

A parking lot now occupies the site where a plaque erected by the RI Reds Heritage Society serves as the only reminder of the decades of entertainment, celebration and rich hockey legacy the building blessed us with.

By RIHHOF