When the RI Auditorium opened in 1926 it was the state’s very first indoor rink. With it, the game’s popularity exploded. Before too long there were too many players, too many teams and too many leagues for the available arena ice time.

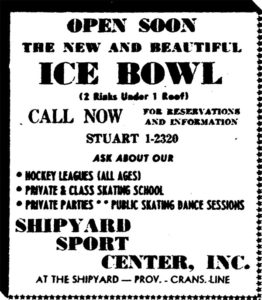

In order to meet their expanding needs, high schools, colleges and local amateur teams continued to rely on frozen ponds and flooded fields and tennis courts to practice, play and scrimmage. It remained that way for another 32 years, until, in 1958, two additional indoor surfaces (one large, one small) opened in the same facility – the Ice Bowl. It was no RI Auditorium, but for several generations of players it was hockey heaven and the training ground for many future collegiate and professional stars.

In order to meet their expanding needs, high schools, colleges and local amateur teams continued to rely on frozen ponds and flooded fields and tennis courts to practice, play and scrimmage. It remained that way for another 32 years, until, in 1958, two additional indoor surfaces (one large, one small) opened in the same facility – the Ice Bowl. It was no RI Auditorium, but for several generations of players it was hockey heaven and the training ground for many future collegiate and professional stars.

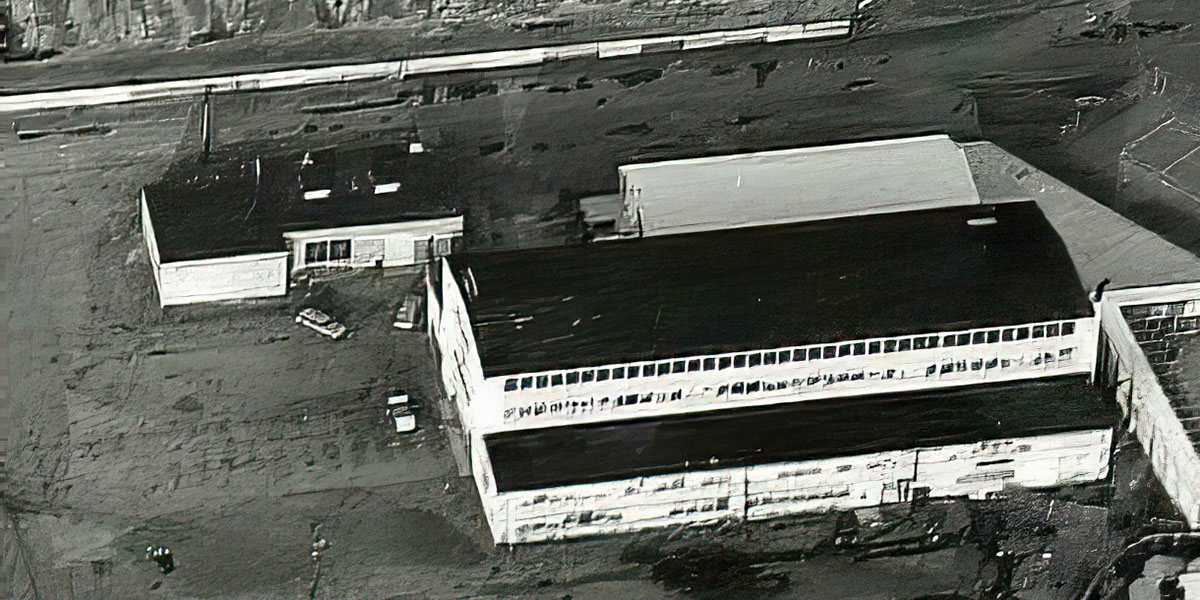

The Ice Bowl was located along the Providence River in the Providence Shipyard, on the Cranston side of the line it straddled with the capital city. It was converted from what had been the shipyard’s machine shop and, for a time, a seaplane hangar.

The structure had been built in 1943 – a large rectangular, steel-framed building used by the Walsh-Kaiser Company in the construction of Liberty Ships, a class of cargo ships. They were built in American shipyards throughout the country to support the war effort between 1941 and 1945. Over that time, the yards produced 2,710 Liberty ships, easily the largest number of ships ever produced to a single design.

The building continued as a machine shop through the Korean War conflict under the shipyard’s manager of 40 years, John “Nehi” Ferreira, father of LaSalle Academy All-Stater, BU All-American, and longtime NHL executive, Jack Ferreira.

After the Korean conflict, the shipyard was purchased by Melvin T. Berry. It was said that Berry was an adventurous developer and the shipyard was surely testament to that spirit.

Renamed the Harborside Industrial Park, he filled the former shipyard acreage with a variety of businesses, especially entertainment enterprises, including a marina, a Polynesian restaurant, a popular drive-in theater, a bowling alley, and, of course, the Ice Bowl. Berry’s well-respected brother-in-law, Leonard Holland, who lived not far from the shipyard in the Washington Park neighborhood, was the building’s first manager.

Despite sentiments that the rinks were not big enough, the lighting not bright enough, and the temperature not warm enough, “It was popular from the very start,” recalled Holland in a 1977 interview with the Providence Journal. “You could fall down and never hit the ice. The place was often skate-to-skate and body-to-body.”

Despite sentiments that the rinks were not big enough, the lighting not bright enough, and the temperature not warm enough, “It was popular from the very start,” recalled Holland in a 1977 interview with the Providence Journal. “You could fall down and never hit the ice. The place was often skate-to-skate and body-to-body.”

Holland left the position in late 1960 when he was appointed RI’s Adjutant General by then Governor, John A Notte, himself a former goaltender at Classical High School in Providence. By the time Len moved on, the Ice Bowl was buzzing with activity from many directions.

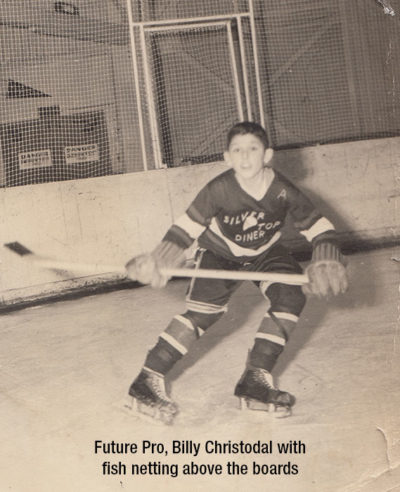

Certainly, part of the Ice Bowl’s immense early popularity had to do with the fact that outside of the RI Auditorium it was the only indoor skating option around and Holland took full advantage despite the Ice Bowl’s relatively small dimensions. The rink surface of its large competition rink was 180 x 55 feet, significantly smaller than the standard 200 x 85 surface. It was also more oval shaped than a standard rink. And where the Auditorium was famous for its chicken wire-on-pipe protective barrier between fans and the game, the Ice Bowl used fish netting.

Despite the shortcomings, Holland maximized what he had. He promoted the formation of new hockey teams and amateur leagues, as well as the organization of new youth programs. He filled the hours with individual and group skating lessons, figure skating clubs, ice skating parties, and public skating sessions on days and at times more convenient than those available at the Auditorium. And he couponed to lure new patrons – regularly offering discounts and even free admissions through cross merchandising offers provided through other entertainment venues, all the while generating additional revenues from rentals, equipment sales, skate sharpening and a refreshments concession.

Ice time was affordable – $25 an hour. The first youth hockey program to take advantage and take up residence at the Ice Bowl was Cranston’s fledgling CLCF program (Cranston’s League for Cranston’s Future), which organized its hockey program there in 1958. The following year, the rink gave birth to the Warwick Junior Hockey Association, which called the shipyard rink their home ice over their first dozen years. Next came the Edgewood Youth Hockey program, founded with the help of former RI Reds great, Harvey Bennett. Some of the players to come out of those three programs in those years would go on to rank among RI’s all-time best.

In 1961, Jim “Butch” Reynolds, one of RI’s finest senior amateur players during the mid-century and well-known to the region’s entire hockey community was hired to take over the managerial reigns at the Ice Bowl. He continued the momentum Holland initiated.

“My dad retired as the manager of the shipyard after the Korean War,” recalls Jack Ferreira. “I skated at the Ice Bowl a few times as a young teenager. I suppose it might have been more if my dad was still on the job,” he quipped. “In high school, Mr. Reynolds would be kind enough to give me and a few of my LaSalle buddies – Lou Lamoriello, Billy Warburton, Dan Sheehan, Tom Fecteau – some free ice time so they could skate and take shots at me.”

“People complained about the Ice Bowl,” said Len Alsfeld, who managed the rink for a time and coached several championship youth teams there over the years. While it never did host a high school or college game due its smaller dimensions, “It was one of the best places to produce hockey players,” Alsfeld asserted, explaining that the smaller rink forced players to be more aware of what was going on around them, requiring them to think, to move, and to pass more quickly and decisively – key assets to being a successful hockey player. And produce good and sometimes great hockey players it did.

The local youth programs, with their quality coaching, were quickly feeding the state’s high schools, especially the locals, with the high caliber talent being bred at the rink. Top of that list was Cranston East, whose teams dominated in the mid-sixties with names like Cavanagh, Bennett, DiMichele, McLaughlin, Tingley, Bryand and others.

The local youth programs, with their quality coaching, were quickly feeding the state’s high schools, especially the locals, with the high caliber talent being bred at the rink. Top of that list was Cranston East, whose teams dominated in the mid-sixties with names like Cavanagh, Bennett, DiMichele, McLaughlin, Tingley, Bryand and others.

Lest we forget about that smaller Ice Bowl rink, it, too, produced some legendary RI hockey figures. Among them, players like David Emma, RI’s only Hobey Baker Award winner, who learned how to skate on that diminutive sheet, and Digit Murphy, who, while attended her older brother’s practices, passed the time on the smaller oval mimicking the boys on her way to becoming an All-American at Cornell and one of the most famous faces of women’s hockey worldwide.

In the spring of 1967, under the administration of Mayor James DiPrete, the City of Cranston expanded its Park & Recreation department through the lease of the Ice Bowl. It was a boon to the city’s young and old, as well as to the high school. At the time, the rink was still home to the CLCF, Warwick and Edgewood youth hockey programs, as well as to the Cranston girl’s hockey program. But time had taken its toll. The fact that the building was never designed for an ice rink was beginning to show and complaints about the Ice Bowl’s physical condition and cold confines mounted. It prompted the city to end its lease in 1969.

Meanwhile, a new spark had ignited regional hockey again. Its name was Bobby Orr. In a matter of just a few years, more rinks were popping up statewide – more modern, more spacious, more comfortable. One of those facilities was Cranston’s own Veterans Memorial Ice Rink on the western side of the city.

During this time, Berry sold the entire Harborside property to businessman David Friedman who closed the Ice Bowl as part of his plan to re-develop the entire port area. “We don’t want the headaches that go into it,” Friedman would say of the Ice Bowl. It remained shuttered for three years before the city renewed its lease in 1972 and re-opened it. Cranston was now supporting two rinks.

For a time it was a working two-rink system with each facility complementing the other – one primarily for local recreation and practices, the other for more serious local and statewide play. But the city could not make the numbers work. In the fall of 1977, Mayor James Taft concluded that maintenance and, especially, energy costs were rising higher than the city could afford and he closed it.

The Ice Bowl was now a memory and a fond one at that. Thousands found enjoyment there over its 20-year run, most especially the dozens upon dozens of players who caught the bug and got their starts in this building, seizing the opportunity to skate and to learn how to play the game, some to even earn scholarships and others to play at the very highest levels of the sport.

By RIHHOF